Archive for November, 2013

CHILDHOOD REVISTED – Gummi Bears

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Childhood Revisited, Television, Writing on November 22, 2013

Statements you will never hear again in your lifetime: in entering the TV animation landscape with Gummi Bears, Disney made perhaps the most unfortunate decision in their entire television history: they made it GOOD.

Have you ever heard of a show that just decided to become good? There are shows where the premise has potential but they seem to always fall short. There are shows with potential that manage to reach it – heck, even surpass it. There are shows with weak premises that somehow become incredible. And, of course, there are shows with weak premises and weak executions. But have you even heard of a show that had a weak premise, became incredible, and because of which made the show more problematic? Is such a thing even possible?

Gummi Bears may have actually achieved this.

Gummi Bears may be the first and only show in the history of television where the marked and genuine improvements of the show worked in the show’s detriment. Not because the improvements were unnecessary, but because young people would not be cognizant or aware of the amount of depth put into the show. Gummi Bears uses its candy-colored (and candy-based) protagonists to appeal to girls and its fantasy setting to appeal to boys (a setting that was quite popular in the mid-80s), but Jymn Magon and Art Vitello, who were tempted to lazily create an adorable preschool-esque show with cheesy names and cheesier lessons, opted for a somewhat grim but ultimately positive tale of swashbuckling heroes, ancient races, mysterious contraptions, calculating villains, and cruel monsters. They were tempted to do Care Bears, but instead made Dungeons & Dragons with teddy bears. The mistake? Care Bears is, at the very least, looked back upon in ironic enjoyment, a workman-like, Hallmark consumer product that sold toys and taught lessons, so whatever. Gummi Bears, on the other hand, surged forward with epic tales and tight storytelling and a broad sense of continuity, and yet relatively few people seem to remember any of this.

That’s the problem. Gummi Bears gets genuinely good. Not simply by improving the animation or voice work, but by creating epic, often-powerful stories and authentically tense moments that rival some of the 90s best television shows. The writing becomes crisp, characters are developed, backstories are explored, history is divulged, and continuity is established. Which, of course, most people would never know. Gummi Bears was years before DVDs and DVRs, before any sense of kids TV shows following an established storyline (the exception might be JEM and the Hologram, which is saying A LOT). The continuity is broad – not nearly as serial as today’s TV shows are – but it’s definitely present, with characters quite often discussing and referring to specific events that happened in prior episodes. Considering, though, that Gummi Bears would have certainly been aired out of order (and with the small attention span of most children), there would have been little chance anyone would have picked up on this. Characters actually grow and change (at least they start to: later episodes seem to diminish earlier developments), but even when Gummi Bears does start to coast, it still manages to create a sense of progress, development, and transformation. But with no way to follow this, Gummi Bears comes off messy, silly and unfortunately forgettable. It’s a deep show masked as a cute show. The irony is that if it WAS just a cute show, it might have been better remembered.

Gummi Bears starts off as you’d expect, with a nice, straight-forward pilot as we follow Cavin and his discovery of the Gummi Bears, who are cute and cuddly, and possess “Gummi Berry Juice,” a liquid that allows them to bounce, because it’s oh-so-adorable to see these bears bounce around. Even though the show makes it a point to establish their different personalities, they’re all stock in trade – Cubbi’s adventurous, Grammi’s motherly, Gruffi’s the “meanie,” Tummi loves food, Sunni is sweet, Zummi is wise if doddering – and there’s a whole thing about a magic book. The pilot, “A New Beginning,” plays lip service to being “last of the Gummi Bears” and the world it establishes, but subsequent episodes of the first season are just what you’d expect. Cubbi and Sunni get into trouble. Tummi’s love for food gets him into trouble. Zummi’s slight klutziness gets him into trouble. There’s a little bit of continuity, what with Tummi’s love for ships and Zummi’s gradually learning spells – but it seems mostly superfluous for whatever cute story the writers cook up.

Then, all of a sudden, the season one finale, “Light Makes Right,” happens:

Nothing says “shit just got real” then depicting an entire population of Gummi Bears running for their lives as their village is destroyed and their homes burn into the night sky. It’s a jarring, momentum-shifting, jaw-dropping moment, made even more dramatic thanks to TMS’s animation, which, I can’t stress enough, is just tops. In this episode, the concept of being the last of the Gummi Bears is given real substance, these six Gummis acknowledging their responsibility to take care of the Glen until the refugee bears can return home. They take note of the uneasy relationship between Gummis and humans, and debate whether its time to call them back. They discover a giant machine that can connect them to these missing Gummis, and they even get a response back. Their hope for a reunion is cut short when Duke Igthorn (who’s backstory, as a former knight of Dunwyn turn betrayer, is explained, making him more than a generic big bad) hijacks the machine and makes it into a weapon. There’s this dark, sad scene where the Gummis, sitting around a fire, shaded in muted shadows, come to the conclusion that they have to destroy the machine, sacrificing their chance to see their people. Watching Zummi desperately grab the final message from the exiled Gummis is legitimately harrowing, giving extra weight to their final mission. It’s a fantastic episode, arguably the best piece of Disney Afternoon animation in its entire lineup.

Gummi Bears immediately takes on new life. The second and third season surges forward with incredible, exciting, and poignant adventures that actually build upon the world and the inhabitants within it. We learn about other Gummi realms and old machines, we learn about Igthorn’s brother, we learn about trolls and orcs, we see Sunni and Toadie connect for a brief moment, we see Grammi and Zummi have a WONDERFUL moment together (in perhaps the richest episode of the run), and they even introduce a new Gummi. It’s remarkable stuff, and even though there are plenty of filler episodes, they work with the context that previous episodes established. Admittedly, they reach a rut in the middle of season four (particularly with Sunni, who they never make into a good, likeable character – she’s always acting bratty to her detriment – and they loose a lot of established good-will with Cubbi), but they introduce the abandoned Gummi capital of Ursalia, Sir Thornberry, Lady Bane, and the Barbic Bears, a sect of Gummis that broke away from the science/magic Gummis to live off the land, giving the show a more rich, well-developed foundation.

DO YOU SEE THIS? Even as I typed out that proceeding paragraph, I can’t still believe all the things this show did and created. All of these well-thought out, clever and rich ideas were present in this show, and it only seems like a few diehard fans would ever know. Not even the living Disney Afternoon crew seems particularly enamored over what they accomplished here (oddly enough they seem strangely mellow over the entire DA lineup, contrasting with the Tiny Toons/Animaniacs cast, who seem rightly proud of their past creation). But Gummi Bears is a fully realized world of fantasy and sorcery and steampunk, of dungeons and dragons – a Lord of the Rings/Game of Thrones-esque show with characters that grow and change.

Take Cubbi for instance. The pink bear with a wooden sword who seeks adventure has all the hallmarks of a safe toy product for the youngest of children, arguably desired pink for girls and adventurous for boys (in an attempt to cross the gender divide). Over the course of the show however, it becomes clear that Cubbi is extremely lonely and feels completely helpless. It seems that bears his age would be in the throes of becoming a knight, but due to being the only living bears around, his life is spent running and hiding. With tales and legends of great Gummis fighting and battling for victory filling his books and lessons, it’s no wonder that Cubbi’s thirst for adventure is at his full force. Age be damned – remember in Game of Thrones, the young character of Rickon watches his father behead a man. So here, in “Up, Up, and Away” when the opportunity comes to leave his family behind to finally become a knight, he takes that chance to finally grow up:

If it was any other set of characters, we’d probably be talking about Gummi Bears today, perhaps in the same cult-hushed tones of praise that we give to shows like Gargoyles or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. But it’s hard for even myself to reconcile my enjoyment and investment in a show that stars six purposely-cuddly teddy bear toys, and this is from a guy who not only enjoyed The Wuzzles, but honestly believes it ought to be rebooted. Other TV shows should be envious of the amount of detail and development that “plagues” Gummi Bears, and can only give nothing but respect to the cast and crew for contextualizing stuffed animals into a fully-fleshed fantasy world – Lord knows how easy it would have been to coast by, considering those first eight episodes.

Yet despite all my reluctance, I have to give Gummi Bears all sincere credit, breaking away from the easy, simple kid stories and make something with richness and depth. It’s rewarding to see, for example, Cavin’s grandfather, who indirectly discovered the Gummi Bears, return and become privy to their existence. Princess Calla grows into her own as she proves herself to be a warrior. There’s real cultural and logistical tension that arise between the Glen Gummis and the Barbic Gummis, depicting two groups that developed differently and therefore have different approaches to how to handle humans. It takes several episodes for them to reach any real accord, and when they do, it feels earned. “The Rite Stuff” and the two part “King Igthorn” series finale finishes the show in pitch perfect fashion. The refugee Gummis don’t return, but there’s hope that the future holds a true reunion between not only all the Gummis, but the humans as well.

Gummi Bears works so much better than you’d think. It’s smart and clever, adventurous and exciting, dramatic and funny, with a few great gags (and a couple of groaners). Yet the real greatness of the show – its overall development of its characters and deep plot continuity – is rarely, if ever talked about. This should change. Whatever you may think of a show with six rainbow stuffed animals at the helm, Gummi Bears was built for fandom culture. Consider me a fan.

Tumblr Tuesday – 11/19/13

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Television, Uncategorized, Writing on November 19, 2013

Welcome to this week’s Tumblr Tuesday! The tumblrs were quiet last week. Perhaps they are getting ready for Friday’s Korra finale? Or Doctor Who’s Day of the Doctor?

— Nickelodeon seems innocent with these accidental pics – but that last one though:

http://totalmediabridge.tumblr.com/post/66850008155/pendulumwing-1overjordan24-sassyfirst

— Really great painting tutorials for explosive effects:

http://totalmediabridge.tumblr.com/post/66850401677/littlecoffeemonsters-pwnypony-makkon

— The only funny Vine ever:

http://totalmediabridge.tumblr.com/post/67193684794/fishingboatproceeds-disgracefullyriversong-i

— And I normally don’t do cat gifs, but this was adorable:

http://totalmediabridge.tumblr.com/post/67286009513/dukeofnod-no-you-fool-you-could-fall

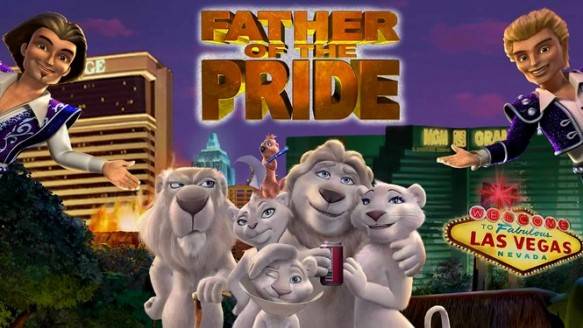

SIMPSONS CLONE ATTACK FORCE, THE LOST SERIES – Father of the Pride

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on November 14, 2013

Early 2000 was a weird moment for television. It was before the critical consensus of our current “Golden Age of TV,” and no one knew what do with comedy (“cellphones ruined comedy” was the running commentary at the time). Seinfeld and Friends ended, and mainstream audiences seemed to want that again; at the same time, the quirky, alt, weird comedies were slowly coming out and making headway with niche audiences but could not make any real splash. This era had Family Guy, Futurama, Dilbert, Home Movies, The Oblongs, Arrested Development, Mission Hill, Clerks: The Animated Series, Clone High, and the Adult Swim lineup, and all but Adult Swim were cancelled. We seemed to want the next Simpsons (the winner of that line of succession was King of the Hill) or the next South Park (the winner of THAT succession was to be Family Guy upon its return). Or maybe we wanted a new Friends (which is currently Big Bang Theory), or the next Seinfeld (Curb Your Enthusiasm, and then Two and a Half Men, unlocked that achievement). The truth was that comedy audiences were splintering, other networks were stepping up their original programs, and it was a creative free-for-all.

Our expectations at the time was bizarre. Comedy wise, we wanted the same thing, but different. We seemed to be unable to judge things on its own merits. Everything was compared to the big four: South Park, The Simpsons, Friends, or Seinfeld. We just would not allow a show to stand on its own. The Oblongs were consistently compared to South Park and The Simpsons, but by now everyone knows how it’s really should’ve been acknowledged in its own right. And we’re all aware how cruelly The Critic was snatched from us – an occurrence we’re paying for today. And nothing represented this more than the fall of NBC’s Father of the Pride, a show doomed by everything by the critical and public thrashing of the aspects around it, and very little had to do with the content of the show itself. Almost ten years removed from that era, can the show stand on its own? A good question, but it’s important to take stock of those occurrences first. History, doomed, repeat it, etc.

—————-

Father of the Pride was destroyed by an onslaught of forces so random and problematic that it seemed God himself had issues with the show about a family of talking lions interspersed with the insanity of two eccentric showmen. At the time, it was the most expensive TV show to ever been produced. The marketing and early reputations emphasized its broad, mature jokes – sex and cursing, basically – something that just didn’t happen in a talking animal show. Critics were quick to point out the Dreamworks connection, bemoaning the inevitable movie tie-ins that were sure to come – hell, a lot of that was derived from the “Donkey from Shrek” guest appearance in episode “Donkey.” And, to make matters worse, the actual Roy from Siegfried and Roy was attacked by his own lions. The show made it to air, but after a critical thrashing and hemorrhaging viewers, the show was immediately cancelled.

I remember specifically not liking it at the time, so upon my rewatch of the series, I expected to be doubly embarrassed. To my surprise, I found myself quite liking it. It occurred to me, as the show passed through my retinas, that comedy, and our expectations of comedy, have changed, and all those original critical complaints that were levied at the show at the time became the norm. The emphasis of sex, gay, and crude jokes; the mindless pot-shots at celebrities; the nonsensical storylines and bizarre plot points – the things that we seemed to hate back then are so engrained in the current comedy climate and are part of the DNA of current critical favorites like The Venture Brothers and Community. And the Dreamworks connection (among other product placement)? Please. Product placement is so common now its to be expected, and crossovers/connections are in effect Adult Swim’s stock-in-trade, and soon to be Disney’s and FOX’s as well.

Father of the Pride isn’t a great show, but it decently funny and rather inspired at times. In some ways, the show is about three people – Larry, the father/husband, Kate, the mother/wife, and Sarmoti, her father – and their increasingly strained relationship to one another. Sierra and Hunter, the children, are really nonentities, points of interests only to serve as reflections of the turmoil between the adults. Among the crude gags – and really, they aren’t crude at all, just occasionally poorly timed – are rather deep and poignant conversations about marriage, love, family, legacy, passion, generational divides, and balancing it all.

The show doesn’t start off on the right foot. Being so egregiously caught up in its own “I can’t believe they’re getting away with this” hype, Father of the Pride’s first episode, “What’s Black and White and Depressed All Over” doubles down on the sex gags, beginning with Kate in heat and a horny Larry wanted to bone her, only to be interrupted by a distressed panda named Foo-Lin who’s alone and depressed with having no mate. So they play matchmaker to a new panda named Nelson, only for him to fall in love with Kate. It’s not exactly a well-plotted episode, and seems more concerned with getting away with talks of intercourse, virginity, and curse words, and it ends with a somewhat grim speech where Sarmoti tells the pandas that, essentially, they’re losers and alone, and they’re the best they’re gonna get. It works, but barely, and seems like a rushed ending to something that wasn’t quite right in the first place.

In relation to the entire show, however, it’s actually a sad speech that acts as a foil to Kate and Larry’s marriage. Early on, in the throes of his romantic/misguided crush, Nelson mentions how Larry doesn’t treat Kate with romantic affection and spontaneity. Kate admits that Nelson has a point, and to my surprise, this theme of a marriage that lost its luster is a constant and decently-handled concept that pervades the show. It’s not great, per se, but it’s there, and relatively consistent. It ends with a Larry trying his hand at singing a Billy Joel song to Kate, who promptly tells him to stop so they can fuck (there’s also a running gag of Larry’s obsession with Billy Joel songs and people telling him to stop singing). Kate is as shallow and flawed as Larry.

This becomes a lot more clearer in “Catnip and Trust,” where both Kate and Larry showcase their distrust and hypocrisy towards Sierra, accusing her of using catnip, only to inadvertently use it themselves. “Possession” is another surprisingly decent episode, where Larry randomly steals a TV from their hated tiger neighbors Blake and Victoria, and Kate covers for him. The thrill gives their marriage a spark – but it really doesn’t, it only makes the sex better. Adding to the complication is seeing Blake and Victoria’s free-wheeling and seemingly healthy marriage, the couple directly embracing and making out on the floor of their own party.

In fact, Blake and Victoria are particularly wonderful characters, over-the-top and melodramatic standouts despite the lack of screentime. Blake (voiced by John O’Hurley) is just an arrogant, attention-seeking wuss, clearly working his ways into the upper echelons of the compound hierarchy less because he cares about the community and more because he loves having an audience. There’s a gag where Blake dresses up chimps in drag while they play instruments. At the time, it was a weird, inexplicable gag, something that seemed to be weird for weird sake. But upon rewatch, it’s funny because it’s Blake – of COURSE he’d do something like this. It’s a dumb visual gag that was more for character than comedy. Hell, in “Larry’s Debut And Sweet Darryl Hannah Too,” Blake sabotages Larry’s show to become lead tiger, only because, as he mentions, just because he craves attention. Larry whoops his ass, but they remains acquaintances; like the Rick James caricature in The Chappelle Show, sometimes you have to physically put Blake in his place, but once there, he’s tolerable. And Victoria (voiced by Wendie Malick, who is a perfectly fine substitute for “old drunken, attention-seeking crone” when Jessica Walters is unavailable) introduces herself to Kate and the audience with the line, “Congratulations! You’re out of vermouth.” (Another attention to detail plot point – the characters leave their front doors open, so people can walk in and out randomly). The show implies they have an open and extremely kinky marriage, and it’s remarkably healthy, especially compared to Larry and Kate, and it’s a pretty remarkable development for a show on NBC.

And the suffering marriage is made worse by Larry’s crotchety father-in-law, Sarmoti, a character who stereotypical badassery is slowly given context over the course of the show, and whose relationships becomes a real source of little expressed tension. Sarmoti at first is a walking one-liner machine, criticizing Larry and the characters in randomly mean ways (“Are we still pretending that he’s not gay?” is a cringe-worthy line, considering its aimed at his grandson), but it becomes clear that Sarmoti was a terrible father to Kate (and budding to be a terrible grandfather to the kids) and is seeking round-about ways to rectify it, along with his fear of losing his manhood and influence. In “Road Trip,” he goes through a hell of time to reunite Larry with Kate, acknowledging how he lost his own wife in a similar way.

Two of my favorite episodes deal explicitly with the sour relationship between Kate and Sarmoti, and also speaks to the show’s strength and weaknesses. “Sarmoti Moves In” quickly sets up the quiet father/daughter rage when Kate, in a fit of unrestrained anger towards her father, rips up and destroyed Sarmoti’s prized possession – the pelt of his best zebra kill when he was living in Africa. In extreme desperation, and one of my favorite plot points of the show, Larry and Kate come dangerously close to killing an innocent zebra to replace it. It’s a great moment, especially hearing Larry and Kate discuss the murder with matter-of-fact dialogue straight-out of an American Dad episode, but it’s limiting because, for some reason, they restrain Kate’s involvement. Considering lionesses are the hunters, it’s a missed opportunity and reeks of networks notes demanding to represses Kate’s viciousness. Still, it opens up the wounds between Sarmoti and Kate, and it’s a dramatic delight to see them so vulnerable.

This happens again in “The Thanksgiving Episode,” when Kate, during PTA elections, casually comments that all turkeys look alike, which causes an social uproar. Here, Father of the Pride’s limits are used as an advantage, as it doesn’t overplay the racial parody hand, making Kate’s attempt to host the turkey’s anti-Pilgrim holiday both awkward and effective, neither overdoing the “racist” or “redemptive” angle. Kate also rails against Sarmoti for filling her head with such a derogatory attitude, at which Sarmoti scoffs; he still believes turkeys are a comically dumb combination of black and Native American stereotypes. The episode ends when a turkey is caught stealing Samorti’s watch, and it’s easy to assume this episode turns back on itself; however, it calls out the lions’ prejudices while also pointing out that turkeys ought to call out their worse members instead of misguided blind support.

This kind of detailed world building for a talking animal cartoon seems unheard of, and passed by most audiences radars, including mine, so it was quite a revelation to see that kind of detail in the show. And it even relates to the sillier portion of the show – the wacky, insane antics of the humans Siegfried and Roy. The more cartoony aspects occur with these two around, with their insane magic tricks and eccentric behavior and talking style. At the same time, they play comic dedication to long-term ideas, like Roy’s innate anger at his unseen father, and Siegfried’s indifference at his man-whorishness. The writers clearly have more comic fun with these guys, and they are funnier, but there’s nothing beyond that, which can be grating if you’re not quite used to that.

I also thought the early TV CGI animation wouldn’t hold up; considering that I watched an episode of Kung Fu Panda: Legends of Awesomeness beforehand, I felt I could explicitly notice the difference. Honestly? It held up quite well. The colors were more muted, and the movements were stiffer and jerkier, but the facial expressions and mouth movements were fine, and after a while you get used to the animation on the whole. The only problematic things are any fast-paced scenes; CGI had yet to perfect the squash-or-stretch or blur movements, so the hit detections and body physics look like shit. But other than the decision to render fur, which kinda works but must have been a pain in the ass to do, the show looks fine and holds up relatively well. But then again, I’m fairly adaptable to different animation styles, so one’s mileage may vary.

In the end, though, Father of the Pride, along with the above-listed brethren, was taken from us before we were ready and willing to see it. I hesitate to say that it was before its time; that implies it has layers of brilliance that the world just did not understand. But in terms of basic tone, style, and sensibility, Father of the Pride was indeed one comic generation delayed, quite before we accepted those aesthetics as the norm. It, like those shows above, aren’t great, but they were a forbearing of things to come.

There is an unaired, unanimated episode called “The Lost Tale,” presented on the DVD and online in animatic form. It continues the show’s direction, with perhaps Siegfried and Roy’s most craziest tale – the sudden desire to build a Jessica Simpson robot – while looking into more of Larry and Kate’s marriage in their approach to their son’s birthday, as well as showing that Samoti’s biggest turn-on happens to be women who genuinely challenge him, like his ex-wife (it’s never made clear if she died or simply left). Perhaps the fan-fiction community can continue this tale, since the show was cancelled, but it’s good to know that, for all the crap leveled against this show, justified or not, it was definitely on the right track.