Archive for August, 2017

The Amazing World of Gumball Recaps: “The End” and “The Dress”

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, The Amazing World of Gumball Recaps, Uncategorized, Writing on August 14, 2017

The Amazing World of Gumball S01E03 The End… by nexusdog1997

“The End” – B

It’s still very early in the show’s run, but The Amazing World of Gumball is starting to show early signs of the kind of confidence and cleverness that it will use to eventually become one of the sharpest and smartest shows on TV. After its introductory episodes, it’s starting to embrace its role as “cartoons about cartoons,” in a way, still focusing on its characters within an animated space and forced into animated plotting. In “The End,” we deal with a classic trope – the belief that the character(s) will be dead within twenty-four hours, so they end up doing all the things that they’ve always wanted to do. Unlike other cartoons, which goes through hoops to “justify” the misunderstanding, or go overboard with those bucket list goals, The Amazing World of Gumball just leans into the sheer stupidity of it all.

I mean, Gumball and Darwin ultimately fall for the mistake by flicking some channels, mistaking a sale sign that says “The End is Near,” and learning about what ancient Mayans thought about solar eclipses. Thus begins their venture into “end of world” fire sale actions, but there’s a number of unique twists to their endeavor – complete with 24-hour countdown clock (and this won’t be the first time they have to deal with that). Darwin wants to actually do good deeds, which is the show’s way ribbing plotlines like this and the selfishness of these characters, particularly with Gumball constant putdowns of Darwin’s selfless desires. Instead, the blue cat finds himself on the verge of going all out, but always being cut short: badmouthing and splashing his teacher with water, for example, forces him to waste three hours of detention. He tries to marry Penny, but she quickly puts short work to that dream. He gets a perm. That’s… it. And there’s something hilarious low-key in how the episode portrays all this – refusing to escalate the intensity of everything Gumball wants to do, it’s creates the opposite affect of what you’d expect. You’d think Gumball and Darwin would be rushing to complete their lives, but everything gets caught in the way.

This even happens when they bring in Richard. Of course he’d believe the boys’ ridiculous claims, but still, the show pulls back from rushing things on purpose. They “need to go faster” in the car but the handbrake is on, and then they crash it, and have to hustle to the store on foot. They’re not even allowed to run in the grocery story! Speedwalking like loons, “The End” just has fun with the idiocy, including a prolonged bit involving a self-checkout machine, and it’s just solid jokes all the way through, even with a porta-potty in the end. There’s a sweet layer to Gumball and Darwin’s final moment on the roof, undercut by the moon literally mooning the sun, in which the two learn the lesson of living life to the fullest. Later in the show, it’ll take that lesson into deeper, more significant places, but here, and in the next episode, Gumball is starting to toy a bit more with its sincerity, its irony, its timing, and its satire.

“The Dress” – B+

Particularly in “The Dress,” The Amazing World of Gumball is really aiming to work on it’s satirical prowess, using a “fame going to one’s head” and pushing it to some wild and hilarious degrees. It never gets personal, nor does it hone in on a specific target like its later episodes, but it does utilize the ol’ “mob crowd” to ridicule how easily people get caught up in… well, anything. “The Dress” leans on a relatively dumb concept – somehow Gumball in a dress is beautiful enough to fool everyone he’s a cute girl from Europe – but the show has so much confidence and commitment to this premise that ends up being kind of weird and wonderful and hilarious. It’s one thing for Gumball to exploit his new-found popularity by forcing his friends to do stuff for them. It’s a whole ‘nother thing to have Darwin fall madly in love with him. His own brother. He’s adopted, sure. But it’s still freaking weird and a bit disturbing.

That “The Dress” invests so heavily in this storyline is part of Gumball’s slow, overall build into something juicier than “funny takes on cartoon tropes.” This feels almost South Park-ian or American Dad-ian in scope. Gumball can’t wear his regular clothes since they’ve been shrunk in the wash by Richard, so he begs Gumball to wear his wife’s wedding dress. Here, there are two growing implications that will build over time: 1) the family’s difficulty with money is implied here (or else, why wouldn’t they just buy new clothing?), and 2) the weird, heighten, psychotic desire for the parents to prove to themselves, and to others, that they are “good” parents in a “wholesome” family and are absolutely normal. Both these points will be so, so important to the overal narrative of Gumball, especially as the show delves into the raw, intense feelings and truths that both those points will expose. Right now, they’re just quiet undercurrents to the show. In the future, they will become immensely significant, so it’s good to see the early bits of that showing up here.

Back to the episode at hand, “The Dress” mostly contorts its weird dumbness into a hilarious story that’s told in a straight-forward, low-key way, just like “The End.” Nothing too over-the-top occurs, in terms of pacing, but Darwin’s growing obsession with fake-Gumball does enter into full-on creep territory. It’s also the funniest part of the episode, although Gumball’s growing awareness of his power as a cute girl – as well as the realization that its gone too far – is also a highlight. I think it’s arguable that Gumball is attempting to make a gendered point about how the world will bend over backwards for attractive women – how his classmates treat him, how his teachers treat him, how Darwin treats him – and I love that at first, Gumball can’t even grasp that concept until Anais points it out to him. That’s when Gumball decides to exploit it, up until Darwin makes a move on the roller coaster, which is so messed up in so many ways, incestuous implications aside. Gumball ends up going through so many things that women have to deal with when it comes to creeps (particularly young women, who find themselves so concerned with “their feelings” instead of their own), and yet in true Gumball fashion, he comes up with an insane plan that gets out of hand.

After a pretty wild fantasy (Gumball trapped in domestic hell with cat/fish surrounding him, with Darwin-as-breadmaker bursting in, demanding more kids), Gumball fakes leaving forever by bus, but his balloon counterpart escapes, flies into the sun, and pops, right in front of everyone. Explaining it doesn’t do the scene justice, but it is such a comical visual that it sort of overcomes the lack of bite the episode has towards it overall thematic point towards the end. That’s okay, though. It’s still testing the waters there, and Darwin immediately falling for a fire hydrant wearing the same dress shows how overwrought the whole venture is in his mind. Gumball is eventually caught with his pants down (or gone, in this case), so he gets his karmic payback in the end as well. “The Dress” is both a play on a classic cartoon trope AND a light dip into blunter satire. It does the former better than the latter, but it’s overall still quite funny, and it’ll get even more confident over time.

The Amazing World of Gumball Recaps: “The Third” and “The Debt”

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, The Amazing World of Gumball Recaps, Writing on August 7, 2017

The Amazing World of Gumball Season 1 Episode… by gumball-amazing

“The Third” – C+

I forgot how “introductory” these early Gumball episodes are. They’re quietly structured around introducing new characters and locations and “things,” like the infamous Dodge or Dare game, which they boys immediately give up on playing. This episode introduces the “school” setting, and a few of the various students in the class. We see most of them – Tina the dinosaur, William the floating eye, Joe the banana, Bobbert the robot, Leslie the flower – but we’re only provided closer looks at Tobias and Alan, and even then they’re mostly one-note at this point. (Tina and Bobbert don’t even have names at this point.) This is a solid episode for introducing the sensibility of the show, which is composed of such an assortment of character and character types, characters who just are what they are and have to exist within that space. This will be more important later, especially as the jokes get deeper and crazier and the show gets more sincere and more satirical. Right now, it’s enough to marvel and be amused by the world opening up a bit.

It’s not that great of a story though, and I can chalk this up to early show “jitters” and the show’s lack of a clear viewpoint this early in the run. “The Third” doesn’t quite know whether it wants to approach its “is Gumball losing Darwin as a friend to Tobias” sincerely, or if it wants to ridicule such a dated and lame trope. The Amazing World of Gumball will get so much better at balancing and bridging those two lines – sincerity and irony – sometimes in the same episode. But for now, this feels like a test. I don’t doubt that “The Third” sees Gumball and Darwin search for a third friend as inherently silly, since it’s instigated because the boys are bored one morning. Later in the episode, when Gumball asks what Darwin wants in a friend, he lists a number of superficial traits: rich, athletic, and “colorful,” as well as “good at listening.” (The last trait, which often is noted as the most important trait in friendship, is clearly tossed off here.) But Gumball’s mad dash to get back his friend feels a little more heartfelt, and even though it’s populated with dumb gags, like breaking through concrete with the power of friendship, it still wants to be honest about it. The issue is that it’s unearned. There’s no realization or cathartic change of heart from Darwin over what he’s done. He just misses Gumball. When he arrive, they hug it out. It feels like something got lost in the narrative.

Still, there are some things to like about this episode. It stands to reason that Darwin would take to Tobias since he did represent all the traits Darwin listed, for better or worse. I’m amused that the show never calls too much attention to Darwin literally buying Tobias’ friendship, even at the expense of Gumball’s own money. The gags are dumb but mostly land, mainly due to how well the show manages the timing of those gags. Bobert’s slow wind up before punching Gumball back is heighten by not showing the actual punch but the hilarious aftermath. The mad dash to Tobias’ house also has a lot of insane bits of visuals, and as I watched it, I’m struck by how well the use of color, backgrounds, and layouts work to really make the show pop, even at this early stage of the show (the hills are a particular highlight). The denouement is the weakest part unfortunately, as Darwin suddenly seems to miss Gumball for no reason, and Tobias lacks any reaction to this point. This also kills the final ironic beat when Darwin and Gumball reject Tobias’ request to play. The blunt, selfish irony of that beat gets lost in the dud of the climax. But it’s practice now, as the show will get much better at this soon.

I want to say one more thing about this episode, but this will be very important for the show as a whole. Gumball’s final race for Darwin is filled with an assortment of obstacles both familiar (biking through wet concrete) and outlandish (a talking wall, and a talking manhole cover). As the show continues, it will slowly start to incorporate a lot of “cartoon-ness” into its worldbuilding, in which its characters-as-cartoons must survive a world in which cartoon tropes, concepts, and meta-concepts are as much obstacles and advantages as anything else in potential narratives. I sort of get into it in this piece about Gumball I wrote years ago, but I’ll explain this in clearer terms as the show gets really comfortable. All you’ll need to know now is this: The Amazing World of Gumball is a cartoon about cartoons; this will make more sense as time goes on.

The Debt – B

Introductions continue as we’re introduced to Mr. and Mrs. Robinson, and (briefly) their son, Robbie. With Mr. Robinson, The Amazing World of Gumball will set up a Dennis the Menace/Mr. Wilson dynamic that will run through the course of the show. I’ve always be a bit aloof about this dynamic. The show doesn’t explain exactly why Gumball (and in the future, Darwin) is so smitten with his neighbor. It sets this up mostly because they know that it will create some hilarious comic scenarios over time – and to be clear, they are hilarious. The situations that bring Gumball to be his most annoying, and Mr. Robinson to be his most frustrated, will create some of the funniest gags in the show’s run. They won’t create many of the more meaningful moments, though, not until they calm Gumball down a bit. One of the things I’m curious about is watching Gumball’s changing level of maturity, if not necessarily his age. That’s one of the limits of this cartoon about cartoons – being “stuck” within a situation and the trappings of cartoon structure (later episodes will make this point more explicit) – but still affecting certain layers of personal growth and change.

Right now though, Gumball is young boy whose fascinations and determinations and energy levels seem endless. It’s the very thing that keeps “The Debt” moving along despite the fact the episode is utilizing one of the older cartoon tropes in the book: the vowed life debt. Gumball perceives that Mr. Robinson somehow save his life (by not running him over with his car, in a situation where Gumball’s life wasn’t even at risk), and swears to watch Mr. Robinson at all costs until he saves his life. It’s an old bit for sure, and Gumball lampshades the idiocy of this story by the non-threatening inciting incident. But it doesn’t do much more than that, still going through the typical beats you’d expect in other cartoons: every time Gumball tries to protect Mr. Robinson, he only makes things worse.

Two things keep this story moving though: the bits they do pull up are very funny, and there’s a weird-but-informative streak throughout the episode that keeps one’s interest piqued. Gumball’s booby trap is just a sudden bit of physical, surprise comedy, and as much as you may cringe with watching Mr. Robinson getting hit in the groin, you might cringe just as much when Gumball is hit in a head by a brick. Anais and Darwin feeling bad for Gumball is kind of out of character, in the sense that Gumball shouldn’t be doing any of this in the first place, but their secondary plot to fake an assassination attempt on Mr. Robinson is great, because it develops its own set of gags and problems, mostly centered around Anais trying to explain the plan to Darwin. And then there’s Mr. Robinson’s final performance, and it’s just so ridiculous, a sort of “release” in case viewers were getting too sympathetic to Mr. Robinson. All that prep, and you’d think Gaylord would have a hidden, glorious singing voice, but it’s just his gruff regular voice, and some 80s aerobic dancing to misplaced fogs and lights. It’s the kind of chaos and misdirection that Gumball is good at, and it’ll get even better.

Gumball does save Mr. Robinson’s life, which is kind of sweet in its own way, up until he pushes Gumball aside to bask in the applause of two old people. Mr. Robinson is a bit… delusional; that and his woes with his wife and son will grow clear and more distinct over time (leading to the darkest moment of the show’s run by far). Still, “The Debt” is a fun watch if not exactly a necessary one, but worth engaging in to see the origins of some the show’s most comedic dynamics – just like “The Third,” really. We’re still getting used to the show’s cast, vibe, and aesthetics, and there’s a value in watching this work in progress.

Dexter’s Laboratory took a simple phrase, and trope, to its logically dark conclusion

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Animation Breakdown, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on August 4, 2017

Dexter’s Laboratory (S1E9) – Doll House Drama… by ClassicCartoonChannel

Dexter’s Laboratory staked its claim in the animation landscape with one simple phrase. It wasn’t a meaningful phrase, and by itself, it wasn’t particularly funny. It’s a phrase that’s pretty innocuous, a nothing of a phrase that nevertheless feels like the culmination of everything the show was trying (and managed) to be. That phrase, you may have guessed, is cheese omelet, or as you would say in French: “omelette du fromage.”

Dexter’s Laboratory is perhaps one of the most important cartoons of the mid 90s, a bold, stark, animated show defined by the direct, specific use of simple shapes, harsh editing, and dramatic visual irony. It’s a show comfortable with a certain “throwaway approach” to character design consistency: characters could change size, even shape, as long as the gags would hit, and hit hard. Dexter’s lab itself always changed, never once looking the same from episode to episode – even how you entered the lab changed through the series (shades of the various, comical ways Perry the Platypus would enter his own underground hideout in Phineas and Ferb). Most animated shows in the post-Dexter’s Laboratory world will mimic or copy the look but not the style, and certainly not the subject, creating a lot of basic, sharp-angled, sloppy shows that more or less were done as a cost-cutting maneuver. Dexter’s Laboratory was (one of the) first, and Genndy Tartakovsky honed his skills here, sharping his timing, pacing, and framing to create iconic sensibilities in the more critically-known Samurai Jack.

We cannot dismiss what Dexter’s Laboratory was doing when hit CN all those years ago. It’s difficult to think about it now, with so many cartoons on the air these days, but even back then the show was playing smart and coy with what kids animation was doing, and could do. It played into a lot of animation tropes, both Western and Eastern, only to undercut them with a narrative twist, a comically sudden beat, or with something so average, so anti-climatic, that you found yourself wondering if you somehow missed the actual ending. Even back then, cartoons were doing some interesting and crazy things, mostly in terms of narrative commitment, but Dexter’s Laboratory looked backwards towards classic cartoon formatting and style for inspiration. Episodes will be split between several shorts, most about Dexter and his family, but other character and show types, including “The Justice Friends” and “Dial M for Monkey.” The rhythms of the entire show will move somewhat like Rocky & Bullwinkle, an assortment of short animated bits, a format mimicked and copied all throughout the Hanna-Barbera era.

Watching the entire episode – which includes “Doll House Drama,” “Krunk’s Date,” and a brief sequence parodying comic book ads disguised as actual comics – I’m struck by the degree in which Dexter’s Laboratory really engages in that classic format. Not just in the ideas of each episode, but even in the stunted movements and somewhat off-kilter edits. The rhythms would definitely be familiar to those who grew up watching something like The Banana Splits or Yogi’s Gang. “Krunk’s Date,” in particular, utilizes a lazy, “limited laugh track” to ostensibly shore up the comedy, but is obviously used ironically here. Dexter’s Laboratory is more committed to its comic beats here than those shows would ever be, and those first two episodes ends on somewhat odd, downbeat gags that feel different than the “sad trombone” gags of its predecessors.

Then we get to “The Big Cheese,” an episode that hilariously steers into its one-note gag to an insane degree – only to snatch it away, hard and without warning. Rewatching this episode, I’m also struck with how patient Tartakovsky builds the gag. Dexter puts off his French homework to work on other, “more important” scientific pursuits, although some are really generic chores with complicated names. There’s no “panic” when Dexter realizes he still has to study – he just decides on a fairly normal trope – overnight osmosis. Playing a record that pipes French-lessons into his ears while he sleeps, the record skips over and over when it hits one central phrase: omelette du fromage. By the 90s, we were well in the CD/cassette era, so Dexter using a record for this feels silly, but it is central to the joke, and Dexter has been shown to disregard a lot of basic ideas for the pursuit of higher intelligence. Obviously his arrogance will prove to be his downfall, but “The Big Cheese’s” idea of a downfall is brutal.

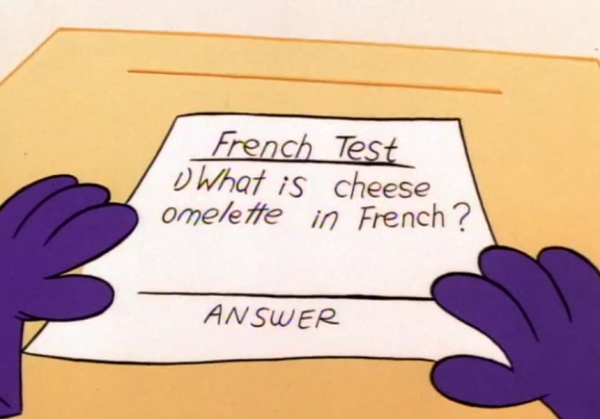

Tartakovsky is fully aware of the trope in play, in how most shows would have its main character work around his situation to avoid being caught in one-phras-only mode. So Tarakovsky immediately has Dexter get caught. It’s by his sister, Dee-Dee, and she begins a comic repetition of her own: “That’s all you can say!” she sing-shouts, over and over, and at this point, it’s amusing. There is also a forewarning nature to it, specifically when she pops up during the montage, a sign of bad things to come. But before that point, that montage is a doozy. Montages are a dime a dozen in cartoons, but here, Tartakovsky escalates the absurdity of the situation with some impressive decision. He even starts the absurdity with a test with one single question, then ramps things up in more and more ridiculous ways. Some are a bit obvious, like omelette du fromage being a French town somehow, and the girls in the class being smitten by his use of French. The potential bullies suddenly being scared off by Dexter’s use of the phrase, however, is such a random development, precisely because unlike the previous gags, this one completely lacks any reason to have occurred.

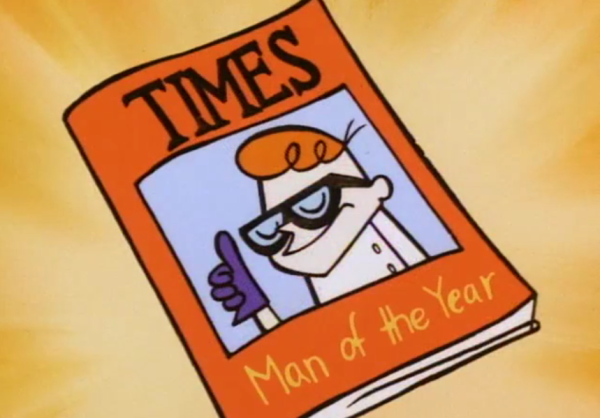

The combination of “maybe this could happen?” and “no way this could happen” results fill up the rest of the montage. Dexter brings world peace. He becomes TIMES Man of the Year. Parades are thrown in his honor. He has a number one hit song that’s composed of, one assumes, just that phrase. It’s so dumb, but there’s a perverse comic value in seeing all the ways Tartakovsky takes this singular bit, pushing and pushing and pushing it to hilarious lengths. And it’s all pretty fantastic… up until the final moments. (I do want to point out that before Dexter enters his home, he kisses a baby, then drops it, as cameras flash. I feel like that’s a key visual sign for the next scene, but I think I’m really over-reading what amounts to a simple, hilarious joke-within-a-joke).

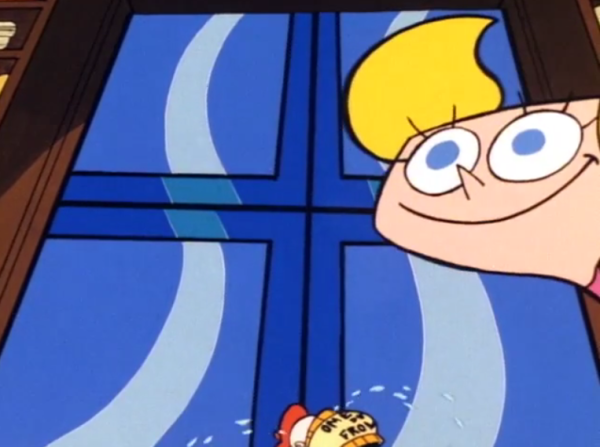

It’s in those final moments though that things turn against Dexter – the karmic, schadenfreude moment that takes thing perhaps too far. Outside his lab, the young scientist learns that his solitary word usage isn’t the password to enter his lab. His computer not only locks the lab up tighter, it begins a self-destruct sequence. Dexter, panicking and in literal tears, shouts in desperation, but only “omelette du fromage” can escape his lips. And then his sister pops up. She begins reciting in comically dark fashion the very phrase she’s been repeating all day, “That’s all you can say.” Unhelpful and useless. And if you were expecting a saving grace, a final reprieve that saves Dexter’s lab and allows the child to learn a lesson in the relative clear… it does not come. The computer says “one.” The lab completely explodes. Dexter and Dee-Dee are visible through a massive hole in their house. Fade to black. THE END pop on screen, “That’s all you can say” echoing silently in the background.

It’s pretty ridiculous in a sense. It’s a cartoon, and developing sympathy for Dexter and his lab, particularly after an episode where he skates by on a French phrase through success after success, comes across as a little weird. Dexter doesn’t really hurt anyone (except that baby, which maybe is worth discussing), and other than his hubris, there’s the question of whether the karmic destruction of his life’s work is proportional punishment to his behavior. It really isn’t his fault that he got famous off the phrase. There’s a lot to be said about the public’s infatuation over such a dumb, singular concept – and I should remind you that this episode took places years before social media and “going viral” was a thing. [I really want to do a piece about how cartoons portray crowds and public reactions; there’s a difference between mob mentality and blindly following a large group for gag purposes.] This is reminiscent of The Simpsons’ “Bart Gets Famous,” in which Bart experiences the highs and lows of success brought about by his own oft-repeated motto “I didn’t do it,” but that show had the time to draw into the reluctance and complexity of Bart’s feelings towards his entire “fifteen minutes.” With “The Big Cheese,” Tartakovsky had three minutes to get to his point, and he focused on the perfect visual display of the rise and fall of success – the fall embodied in a dark, destructive moment that shocked a young generation.

Perhaps “proportional punishment” isn’t really a thing. Sometimes you find yourself so caught up in something that you fail to realize how far you are from the things you once held dear – and they’re gone in an instant. Tartakovsky made his point clear, and it left many people with only “omelette du fromage” and “that’s all you can say” dancing in their heads, in the midst of a dark, music-less void. The very premise of the show, Dexter’s Laboratory, was gone in an instant, leaving kids to wonder if, and why, such a bleakness was warranted. As an adult, we wonder about it still.

NEXT: Rescue Rangers’ uses a badass Gadget Hackwrench to contemplate the value of religion in “The Case of the Cola Cult.”