Posts Tagged Comedy

Dexter’s Laboratory took a simple phrase, and trope, to its logically dark conclusion

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Animation Breakdown, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on August 4, 2017

Dexter’s Laboratory (S1E9) – Doll House Drama… by ClassicCartoonChannel

Dexter’s Laboratory staked its claim in the animation landscape with one simple phrase. It wasn’t a meaningful phrase, and by itself, it wasn’t particularly funny. It’s a phrase that’s pretty innocuous, a nothing of a phrase that nevertheless feels like the culmination of everything the show was trying (and managed) to be. That phrase, you may have guessed, is cheese omelet, or as you would say in French: “omelette du fromage.”

Dexter’s Laboratory is perhaps one of the most important cartoons of the mid 90s, a bold, stark, animated show defined by the direct, specific use of simple shapes, harsh editing, and dramatic visual irony. It’s a show comfortable with a certain “throwaway approach” to character design consistency: characters could change size, even shape, as long as the gags would hit, and hit hard. Dexter’s lab itself always changed, never once looking the same from episode to episode – even how you entered the lab changed through the series (shades of the various, comical ways Perry the Platypus would enter his own underground hideout in Phineas and Ferb). Most animated shows in the post-Dexter’s Laboratory world will mimic or copy the look but not the style, and certainly not the subject, creating a lot of basic, sharp-angled, sloppy shows that more or less were done as a cost-cutting maneuver. Dexter’s Laboratory was (one of the) first, and Genndy Tartakovsky honed his skills here, sharping his timing, pacing, and framing to create iconic sensibilities in the more critically-known Samurai Jack.

We cannot dismiss what Dexter’s Laboratory was doing when hit CN all those years ago. It’s difficult to think about it now, with so many cartoons on the air these days, but even back then the show was playing smart and coy with what kids animation was doing, and could do. It played into a lot of animation tropes, both Western and Eastern, only to undercut them with a narrative twist, a comically sudden beat, or with something so average, so anti-climatic, that you found yourself wondering if you somehow missed the actual ending. Even back then, cartoons were doing some interesting and crazy things, mostly in terms of narrative commitment, but Dexter’s Laboratory looked backwards towards classic cartoon formatting and style for inspiration. Episodes will be split between several shorts, most about Dexter and his family, but other character and show types, including “The Justice Friends” and “Dial M for Monkey.” The rhythms of the entire show will move somewhat like Rocky & Bullwinkle, an assortment of short animated bits, a format mimicked and copied all throughout the Hanna-Barbera era.

Watching the entire episode – which includes “Doll House Drama,” “Krunk’s Date,” and a brief sequence parodying comic book ads disguised as actual comics – I’m struck by the degree in which Dexter’s Laboratory really engages in that classic format. Not just in the ideas of each episode, but even in the stunted movements and somewhat off-kilter edits. The rhythms would definitely be familiar to those who grew up watching something like The Banana Splits or Yogi’s Gang. “Krunk’s Date,” in particular, utilizes a lazy, “limited laugh track” to ostensibly shore up the comedy, but is obviously used ironically here. Dexter’s Laboratory is more committed to its comic beats here than those shows would ever be, and those first two episodes ends on somewhat odd, downbeat gags that feel different than the “sad trombone” gags of its predecessors.

Then we get to “The Big Cheese,” an episode that hilariously steers into its one-note gag to an insane degree – only to snatch it away, hard and without warning. Rewatching this episode, I’m also struck with how patient Tartakovsky builds the gag. Dexter puts off his French homework to work on other, “more important” scientific pursuits, although some are really generic chores with complicated names. There’s no “panic” when Dexter realizes he still has to study – he just decides on a fairly normal trope – overnight osmosis. Playing a record that pipes French-lessons into his ears while he sleeps, the record skips over and over when it hits one central phrase: omelette du fromage. By the 90s, we were well in the CD/cassette era, so Dexter using a record for this feels silly, but it is central to the joke, and Dexter has been shown to disregard a lot of basic ideas for the pursuit of higher intelligence. Obviously his arrogance will prove to be his downfall, but “The Big Cheese’s” idea of a downfall is brutal.

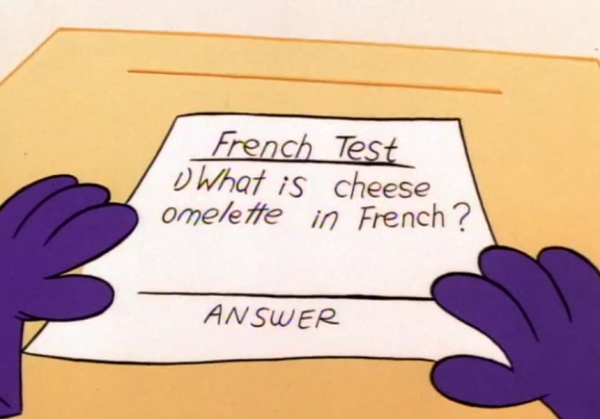

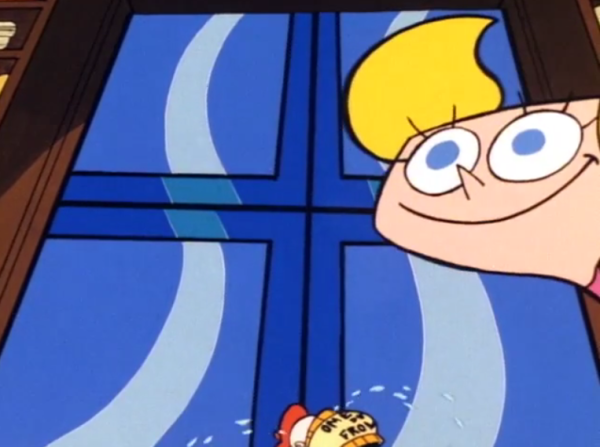

Tartakovsky is fully aware of the trope in play, in how most shows would have its main character work around his situation to avoid being caught in one-phras-only mode. So Tarakovsky immediately has Dexter get caught. It’s by his sister, Dee-Dee, and she begins a comic repetition of her own: “That’s all you can say!” she sing-shouts, over and over, and at this point, it’s amusing. There is also a forewarning nature to it, specifically when she pops up during the montage, a sign of bad things to come. But before that point, that montage is a doozy. Montages are a dime a dozen in cartoons, but here, Tartakovsky escalates the absurdity of the situation with some impressive decision. He even starts the absurdity with a test with one single question, then ramps things up in more and more ridiculous ways. Some are a bit obvious, like omelette du fromage being a French town somehow, and the girls in the class being smitten by his use of French. The potential bullies suddenly being scared off by Dexter’s use of the phrase, however, is such a random development, precisely because unlike the previous gags, this one completely lacks any reason to have occurred.

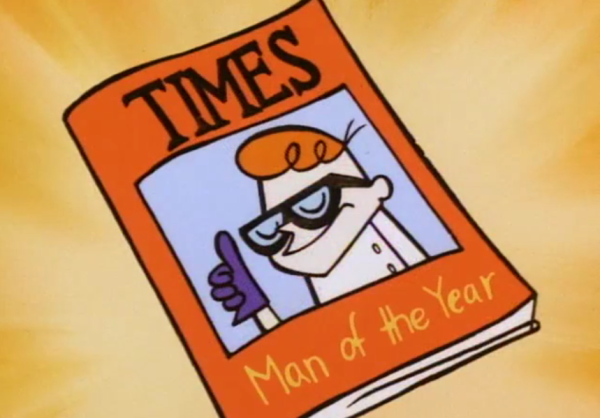

The combination of “maybe this could happen?” and “no way this could happen” results fill up the rest of the montage. Dexter brings world peace. He becomes TIMES Man of the Year. Parades are thrown in his honor. He has a number one hit song that’s composed of, one assumes, just that phrase. It’s so dumb, but there’s a perverse comic value in seeing all the ways Tartakovsky takes this singular bit, pushing and pushing and pushing it to hilarious lengths. And it’s all pretty fantastic… up until the final moments. (I do want to point out that before Dexter enters his home, he kisses a baby, then drops it, as cameras flash. I feel like that’s a key visual sign for the next scene, but I think I’m really over-reading what amounts to a simple, hilarious joke-within-a-joke).

It’s in those final moments though that things turn against Dexter – the karmic, schadenfreude moment that takes thing perhaps too far. Outside his lab, the young scientist learns that his solitary word usage isn’t the password to enter his lab. His computer not only locks the lab up tighter, it begins a self-destruct sequence. Dexter, panicking and in literal tears, shouts in desperation, but only “omelette du fromage” can escape his lips. And then his sister pops up. She begins reciting in comically dark fashion the very phrase she’s been repeating all day, “That’s all you can say.” Unhelpful and useless. And if you were expecting a saving grace, a final reprieve that saves Dexter’s lab and allows the child to learn a lesson in the relative clear… it does not come. The computer says “one.” The lab completely explodes. Dexter and Dee-Dee are visible through a massive hole in their house. Fade to black. THE END pop on screen, “That’s all you can say” echoing silently in the background.

It’s pretty ridiculous in a sense. It’s a cartoon, and developing sympathy for Dexter and his lab, particularly after an episode where he skates by on a French phrase through success after success, comes across as a little weird. Dexter doesn’t really hurt anyone (except that baby, which maybe is worth discussing), and other than his hubris, there’s the question of whether the karmic destruction of his life’s work is proportional punishment to his behavior. It really isn’t his fault that he got famous off the phrase. There’s a lot to be said about the public’s infatuation over such a dumb, singular concept – and I should remind you that this episode took places years before social media and “going viral” was a thing. [I really want to do a piece about how cartoons portray crowds and public reactions; there’s a difference between mob mentality and blindly following a large group for gag purposes.] This is reminiscent of The Simpsons’ “Bart Gets Famous,” in which Bart experiences the highs and lows of success brought about by his own oft-repeated motto “I didn’t do it,” but that show had the time to draw into the reluctance and complexity of Bart’s feelings towards his entire “fifteen minutes.” With “The Big Cheese,” Tartakovsky had three minutes to get to his point, and he focused on the perfect visual display of the rise and fall of success – the fall embodied in a dark, destructive moment that shocked a young generation.

Perhaps “proportional punishment” isn’t really a thing. Sometimes you find yourself so caught up in something that you fail to realize how far you are from the things you once held dear – and they’re gone in an instant. Tartakovsky made his point clear, and it left many people with only “omelette du fromage” and “that’s all you can say” dancing in their heads, in the midst of a dark, music-less void. The very premise of the show, Dexter’s Laboratory, was gone in an instant, leaving kids to wonder if, and why, such a bleakness was warranted. As an adult, we wonder about it still.

NEXT: Rescue Rangers’ uses a badass Gadget Hackwrench to contemplate the value of religion in “The Case of the Cola Cult.”

The Amazing World of Gumball Recaps: “The DVD” and “The Responsible”

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, The Amazing World of Gumball Recaps, Writing on July 31, 2017

I’ve been wanting to do episodic recaps for The Amazing World of Gumball for a while now. I’ve tried to convince a few of of the websites I freelance for to cover this show, but it never catches on. In the past year or two, the show has been gaining massive popularity – somewhat unfortunately, in the “I can’t believe they went there” fashion, but there are those who recognize it for its boldness, brilliance, cleverness, sharply dynamic animation, and flawed, enriching characters. Since mainstream critics won’t call attention to it (while frustrating, I do get it), I decided to tackle the show myself. I’m looking forward to it, especially as the show breaks from its original basic setup into a harsh, powerful, dramatic satire of a surprisingly put-together world.

The Amazing World of Gumball Season 1 Episode… by gumball-amazing

“The DVD” – B+

The Amazing World of Gumball will take some time to get to that point. It won’t push boundaries, or raise stakes, or truly commit to the honest, raw, and genuine emotional state of its central characters until some point in the second season. By that time the animation will have changed, and with that, a clearer observation of who and what the characters and the world of The Amazing World of Gumball can be. But we shouldn’t discount what occurs in “The DVD.” The basic, core characterizations are here: Gumball is the awkward kid who’s blindly committed to bad ideas, Darwin is the nice brother who cowtows to Gumball’s whims while simultaneously tries to talk him out of it, and Nicole, Gumball’s mother and the show’s early and continuous standout, is the stereotypical mother figure with a hilariously overbearing, militant streak. The show will complicate those attributes further overtime. But for now, “The DVD” is a basic fun lark, a taste of things to come.

One fascinating thing is that the characters feel fully realized, if not fully formed, in the early going. The opening exchange, that very first joke of escalating passive-aggressiveness between Gumball and his mother, immediately provides the early glimpses of the specifics of the characters, and even a sense of the type of show The Amazing World of Gumball will end up being. The final line, in which Gumball suggests that this entire issue with the DVD is Nicole’s fault for having kids in the first place (and before Nicole showcases her iconic, individual strength by punching through a wall), hints at a level of adult humor that the show will grow more and more comfortable in utilizing as the show goes on. I’ll need to make a point though – “getting away with adult jokes” is not at all what Gumball should be recognized for.

No, the juicier material lies within the entire scenario in which Gumball and his brother Darwin attempt to avoid “the consequences of their actions” and attempt to return a fake DVD and ensure their mom never learns about it. It’s cartoony basics here, with jokes like a fake cardboard DVD, Darwin speaking a long line in Chinese that’s translated as a simple “No,” and an amusing scene in which Gumball finds himself deeply allergic to makeup. Yet Gumball will also get a bit harsher with its satire, like the scene in which the two lower-middle class brothers beg on the street next to an an actual homeless man. It’s a dark, pointed gag, in which the homeless man not so subtly points out the insanity of the situation. It’s also pretty fucked up that the implication is that Gumball and Darwin received more change than the person who actually needed it (symbolized by a ridiculous beatboxing scene, where the two siblings once again get change over the homeless man). Karma comes quickly once the man takes the change buys a scratch-off, and wins; when Gumball then asks for his four dollars back, the formerly-homeless man feigns no longer having any change on him. It’s brutal, especially once it becomes clearer that the Wattersons aren’t quite wealthy in their own specific ways, and Gumball will get incredibly more direct on this point later in the series.

The ending sequence is also a perfect taste of what Gumball will improve upon as the show goes on as well – an epic chase scene in which Nicole runs – and I mean runs – after her children in anger from the lies. Even this early in the animation, it’s a visual masterpiece, with an action-movie sensibility to the aesthetics, and props to making it clear that Nicole’s rage, while epic, can be on occasion hindered. It ends on a couple of generic but hilarious gags and tropes – Larry watches the DVD and sees a terrible Sweded version of Alligators on a Train, Nicole hears the confession and declares her love for them is universal, and she pays the $25 fee for the DVD. But then the Gumball goes for what will mostly be its signature move, the ironic ending, the narrative switch that will keep viewers on its toes: when the late fees add up to a whopping $700, Nicole, nice, calm, and loving, tell her children to RUN. It’s perfect, a symbolic freeze-frame shot that sums up the show in a nutshell.

“The Responsible” – B

“The Responsible” introduces Richard Watterson and Anais Watterson. Both characters will go through some changes and deepening over the course of the show, particularly Richard, who will take a quite a while to make into a more workable character. Richard here is portrayed as the bumbling idiot, the comic relief who hates pants and whines like a manbaby. The Amazing World of Gumball as this point is still in its infant stages. It won’t really grasp its identity as a firm, (hyper)realistic, (dys)functional family until later. Right now, it’s mostly separate characters that are a family in name and gags only. Richard is a joke and Nicole is a machine, and Darwin and Gumball are the two who get into various scrapes. In this case, it’s how they take care of their baby sister, Anais, after Richard screws up in ordering a competent babysitter.

Anais is more solidified as a character. She will get even better, more or less contrasting her underrated genius and strategic thinking with her abject loneliness, youthful desperation, and the limits of her self-reliance. Here she has to struggle with her idiotic brothers as they go overboard with their protectiveness. She can’t watch TV (or specifically, commercials) because they’re corrupting, so she gets to witness Gumball and Darwin bash the TV set to death with bats. She can’t read a book, because she might get paper cuts, so Darwin jumpkicks it out of her hands. She can’t eat solid food (what her siblings pass as food anyway), so they chew it up and give her the chum. Rightfully, she knocks it back into their faces.

“The Responsible” is a fine, even visually great episode, with some great little details to keep your attention. It’s a great showcase, for example, when Darwin swims in the flooded house with ease, reminding you that he is indeed a fish (who enjoys his fishchips now and then). A steady shot in which Darwin and Gumball chase Anais around the living room is fantastic, mostly because it allows the space to be utilized in a lot of fun ways, sans cuts or edits. It doesn’t get a chance to get much deeper or exploratory though, mostly as an episode to enjoy the fruits of its animated labor. Its most cartoony moment is when they three pop out the chimney in a geyser and land hard on the sidewalk below, with only scratches. Yes, this is a cartoon, so this is a difficult line to walk, but while at this point The Amazing World of Gumball is more Looney Tunes, it’ll gradually pull away from that tone just enough so that stakes and threats will be harsher and more dangerous, eventually mastering it perfectly.

“The Responsible” also gets into Gumball’s narrative self-awareness, as this episode is all about the value and importance of responsibility (similar to “The DVD,” which is also why it’s a step down since it’s more or less a thematic retread). The lesson is learned, after a hellish experience, and the point is made when Gumball eventually accepts taking responsibility for the chaos… only to be unable to commit to it after staring into the flaming eyes of his mother. Gumball undercuts its lesson learning as every character ends up blaming something else for the disaster, eventually settling on the internet, which is part and parcel of the show’s ironic endings. But as the show goes along, that kind of undercutting will end up reaching some real, raw revelations that go being childish lesson learning, revelations that will be twice as significant as the basic ones. Claiming the internet is at fault is the show’s way of exploring the tendency of people to absolve themselves by pointing towards others who messed up (whataboutism), but The Amazing World of Gumball in time will provide much more bite to those kinds of endings. Which leaves this ending okay for what it is, especially this early in the show’s run, but once Gumball gets a firmer command on its voice, the perfect interplay with biting cynicism and genuine optimism, it’ll truly become one of television’s sharpest, most hilarious, most biting, and most effective programs.

Some Brief Words on Penn Zero: Part-Time Hero

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on July 28, 2017

The premise of Penn Zero: Part-Time Hero doesn’t make any sense. A boy and his friends, who all still attend school, head into an abandoned theater where they are warped into alternate dimensions, take the role of some kind of protagonist/leader (and their sidekicks/lackeys), and have to accomplish some grand objective. When they do this, they (apparently?) take over the bodies of characters that already exist in that world. They also have to face a set of antagonists/villains that are controlled/taken over by their art teacher and school principal. When they return home, everything is back to the way things are – as normal as things could be. There’s a lot of questions. How did a bunch of kids get into the gig of interdimensional body-control and part-time heroics? (Penn, arguably, got into it through his parents – more on this later – but his sidekicks Sashi and Boone are occupational enigmas.) What happens to the people when they take over their bodies? What about Rippen and Larry? Who is Phyllis, the lady who controls the portal machine? What signals a particular world that needs heroics? Why would a world need competing villains? How long has all this been going on? And why?

I think that most of these questions were meant to be answered – or least explored – over the course of several seasons. It only received two. And as Penn Zero ends its two season run today, we’re given all the answers we’ll ever get (bearing an unlikely comic or graphic novel followup). In a way, it’s fine. The second season of Penn Zero did little about answering those big questions, and focused on smaller, personal bits of characterization – and exaggerated cartoon satire in the midst of broad, insanely creative alternate dimensions. The show scrambled together a brief, clearly-rushed season arc in which Penn had to find some crystal shards so Phyllis can track where his parents are (also part-time heroes), an arc that gets its due only in four of the final fourteen episodes. It spent most of its other episodes either revisiting past worlds with new, more intense objectives, or finding themselves in new locales with more ridiculous, almost nonsensical ones. Penn Zero, in its remaining season, culled together final episode pitches with an assortment of ideas that seem geared for a multiple seasons. It treated its second season as if it was its fifth season.

There’s something bold about that, though. I mean, if you’re forced to end your show a bit prematurely, you might as well throw all your best ideas out there. It may be too many ideas though. Episodes feel overrun at times, like Penn’s return to a world of dragons that, in the first season, just doubled as a Top Gun parody. The team’s second appearance incorporate elements from Star Wars, Aliens, My Little Pony, and a host of other pop culture references that I recognized. There’s also a lot of wink-winking towards animation tropes, like a hilarious anime-parody episode, a sitcom-bashing one, and one that engaged in a classic cat-and-mouse chase cartoon, similar to Tom & Jerry. Some episodes are just plan weird: the cast returns to a world where everyone is some kind of sport ball, literally, and it includes Curtis Armstrong as a super bouncy ball with serious insecurity and anger issues for some reason. An episode that checks in on Penn’s parents includes a fire-breathing giant chicken, a sketchy city inside the belly of said chicken, a sleazy pickpocket with an eyeball for a belly and lips for a head (voiced my Marc Maron), and mafioso, flamethrower-wielding grandmother with zombie cat demons for henchmen. This… is a weird show.

Speaking of which, the situation with Penn’s parents form the backbone of the show’s arc. They’re trapped in that bizarre world mentioned in the previous paragraph, and Penn has to recover three shards of… something to bring them back. It’s not exactly a tightly-scripted story arc – the retrieval of the first shard is accomplished during a weird random end tag, involving a giant Phyllis, which raises even more questions (and I know I’m skipping a lot of explanation here, but the episode has Penn deciding whether to go after the shard or save the day, and it doesn’t explain why Penn doesn’t just go after the shard after saving the day, or coming back to this world just a bit later). It does however delineate high-level stakes to these final episodes. There is pretty strong theme of loyalty, heroics, and sacrifice, especially between the roles of parental and childish figures, but fourteen episodes are not nearly enough to delve into them. Still, Penn Zero went ahead and did it anyway, which requires some balls.

You can’t help but wonder if Penn Zero: Part-Time Hero was meant to be the popular followup to Phineas and Ferb, another show that involved a weird-looking red-haired kid and random forays into strange places (that now looks to be Milo Murphy’s Law, a show that needs to explored at another time). Disney XD was going through some issues, and a lot of two season shows got shut down (including the delightful Wander Over Yonder and the not-so-delightful 7D). I don’t know if Penn Zero needed, or deserved, more time to flesh itself out. It was funny and clever enough, the characters were perfectly, comically realized (Sashi (Tani Guadi) was the overall show standout but second-season Penn (Thomas Middleditch) came up strong), and it clearly had a blast coming up with some of the alternate dimensions and the plots that took place in them. It felt like it got so caught up in that creative freeform that it never took the time it needed to really let its characters, and its specific in-world logic, explain itself.

That’s not necessarily bad. Lots of shows don’t make sense and thrive on that concept: Archer is purposely anachronistic, and Phineas and Ferb enjoyed its creative freedom. The latter show also knew to keep its central concept basic – a couple of kids just trying to find something to do during summer vacation – so when things did get crazy, it could count on cartoon logic to carry it through. Penn Zero often relies on cartoon logic as well – with plenty of self-aware, forth-wall gags, like when a Penn-as-kaiju destroys a “Rule of Thirds” Store on his third accidental stomp – but it’s too ingrained into its emotionally-charged backstory to escape from it. What happens if a hero fails – or worse, dies? That threat looms over the show, if never taken seriously whatsoever. Still, it’s possible, and I almost feel like the show would have been better off ditching any semblance of a season arc all together.

Still, Penn Zero: Part-Time Hero is just weird enough, funny enough, and creative enough to check out its final run, and its assortment of solid guest starts is also wildly impressive, which includes Mar Maron, Mark Hamill, Maria Bamford, Kumail Nanjiani, and Yvette Nicole Brown. Mercury Filmworks and Disney Television Animation pushes the paper-like-cutout designs in some striking ways within the animation, both large and small: large-scale, sweeping movements are as grandiose as some small, detailed facial expressions are hilarious. Penn Zero is a fun lark, and it’s somewhat sad to see it go “before its time,” but in some ways, it’s for the best. There’s too much going on that shouldn’t really be going on, and it’s better to end it before it reaches fan-theory status.

FINAL THOUGHTS ABOUT THE FINALE: If anything, “At the End of the Worlds” confirms the idea that Penn Zero: Part-Time Hero is probably better off ending now instead of continuing, even despite the fact it thrived with potential. It committed to a weirdness that felt more egregious than necessary or clever, and I’m not exactly talking about the revelation that Phil and Phyllis were separate entities of some kind of intergalactic time-space being gloriously entering Phase Two of some cosmic mission (I swear this is all true). You could argue, in a way, that the episode was parodying a lot of tropes of various grand finales: Boone sacrificing an “upgrade” for the sake of the team; a final fight with evil clones, with Sashi exploiting a weakness that she developed for years; an epic battle among the heroes and villains of the various worlds that Penn and Rippen visited in the past. It had an almost-at-peace death scene when Penn nearly falls to his death and reminisces about his parents. It had an almost-ironic parents-return-only-to-have-to-go-back-for-some-lame-reason (the show even lampshades its stupidity) moment. It had a “Rippen becomes good” sacrifice, only to be undercut by a bunch of random characters joining him. And then there’s the Phil/Phyllis thing, which played to the idea of needing a good/evil balance in the multiverse – although the show never really thematically supported that idea. It is… a lot, and I’ll always respect the hell out of the show just fucking doing all that, but I can’t exactly say we missed out on something grander. It is what it is, and kids will have their first(?) taste of something cerebral and mind-blowingly out-there. Beyond that? Nothing more revealing than a forced Penn/Sashi romantic pairing. So much for fan-theories.