Posts Tagged Comedy

Warner Brothers’ Storks Film Carries More Weight Than Just Babies

Posted by Admin in Animation, Film, Uncategorized, Writing on June 14, 2017

Storks received some minor attention when a Twitter account pointed out a montage from the film showcasing various couples – and singles – receiving babies from the flying avians. The recipients were of various races, ages, sizes, and sexuality. It was a slight scene, and it was really only for those who would take notice, but it still was worthy of attention. Storks seems like it’s part of the not-so-great trend of films playing minor favors towards progressive ideals – a sentiment that feels more like a “spot the trend” game than any real sense of modern acceptance of diversity. Storks, a movie as a whole though, is genuinely more interested in those progressive ideals than a tossed-off montage. Storks is generally dismissed as a non-essential children’s film. But it’s a funny, clever, self-aware bit of animated goofiness with its heart firmly held in its silent, but meaningful, progressivism.

Storks, at the onset, feels like its a film about nothing, really. It’s the off-beat, quirky story of a stork at a company, which no longer delivers babies, teaming up with a orphan human girl, to do just that. The movie runs through an assortment of wacky set-pieces and silly characters via a plot that on its surface is rather simplistic and superficial. Its reliance on heavy cartoony antics and self-aware gags can be a turn-off to a lot of people who prefer their animated films to be more grounded and sophisticated (an approach I find limiting in a lot of ways but that’s a topic for another day). Yet underlining all of that silliness, Storks exhibits a real sense of confidence in its characters and in its setting – a confidence that is exploratory and distinctive, noticeable with a closer look.

I hate saying this, and I hate how this will sound, but I need to say this only in order to clarify it: Storks is arguably the most “millennial” movie I’ve seen in a while. It’s a film in which its absurdity and irony attempts to, but doesn’t quite, mask its dramatic exploration of the confusion of life and complications that younger “20-somethings” face. It’s a film that comically but quietly explores their contemporary search for purpose and identity – in a wildly basic way, but in a way that feels necessary. Storks wears its heart on its sleeve. It is quietly, narrowly honest, but that honesty is cluttered in self-awareness, funny voices, and physical comedy – the kind of way in which millennials tend to approach their futures.

It’s tricky, almost dangerous, to explain myself without stereotyping, but hey, I certainly wouldn’t be the first critic to speculate on “what millennials are” these days. In my experience, I find that this particular upcoming generation is more honest and forward than the previous one, but often diffuses that honesty through irony, asides, and forced comedy. (You know, memes.) Storks isn’t a “meme” movie, in that it didn’t inspire an array of JPEGS and GIFs tossed about on social media, but its core sentiment is easily lost in its nonsense. One could suggest that the film’s failing is exactly that – its sentiment is belittled by its chaotic cartooniness. But I feel like that’s a shallow reading of cartoon antics in general, an implicit denial of letting cartoons be cartoons. That is to say, all of those antics don’t deny the film’s sentiment, even if the characters aren’t the utterly raw, broken characters, like the ones in Bojack Horseman or Rick and Morty. The cast of Storks are lost in deeply confused, deeply aimless ways, composed of characters who are coded in youthful exuberance and confidence but not necessarily a purpose: Junior the stork (note the name) is up for promotion without any idea as to what to do when he gets it, while Tulip the human is a literal 18 year-old orphan who has no idea who she is or where she belongs.

Storks is somewhat atypical of most animated movies in that it places much of its stock on those two characters for a good portion of its runtime. All the physical gags and loose plotting is secondary to the film’s confidence in the interplay between Tulip and Junior, and essentially the voice artists Katie Crown and Andy Samberg. And it is a delightful pairing. Crown and Samberg work off each other so well that it almost feels like certain scenes were added and/or extended just to pad their interaction. Their comic conflicts and camaraderie move fast and sharply, due to the power of two actors on top of their game. Yet even through those comic interactions, Samberg and Crown don’t deny or ignore the complication of their characters in this weird, specific moment in their lives; they instead manage to exude their current turmoil through their hilarious performances. It’s not nuanced, but millennials aren’t particularly nuanced (and I mean this positively). Just because someone posts a meme that dumbly describes their current feelings doesn’t negate the fact that they’re indeed feeling that feeling.

It’s immediately present early in the film, when Tulip gleefully asks Junior to stop calling her “orphan Tulip”; she comically, but bluntly, describe how the term “hurts her heart.” Later in the film, Tulip teases Junior over his ideas on what he would do once he’s promoted. After a bit of inane, silly prodding and subsequent deflections, Junior reacts in anger: “BACK OFF” he screams. It’s a hilarious but personal response to his dilemma – what does he truly believe in? What is his personal drive upon “earning” his position, and what will he do when he achieves it? Junior is terrified of self-reflection; throughout the film, he blindly recites the corporate slogan, he sings the commercial jingle to a baby, and he grows excited over Storkcon, a convention in which its cleverest innovation is a spherical box.

I don’t think millennials aren’t especially hostile to capitalism, so much that they’re more readily and willing to question and criticize it. “Climbing the ladder” is still the goal of many young people, but as it becomes clear that such an achievement is more complex and fraught these days (financially, socially, and mentally), millennials at the very least need a real sense of purpose within the system that goes beyond “it’s just what you do.” Junior’s mind literally explodes when he gets that promotion early in the movie, yet the story showcases his reluctance to articulate what, exactly, he would want to do once he achieves this. Tulip’s assured ideas push back against Junior’s smarmy question over what she would do in his position, but it also reinforces how specifically lost Junior is in this particular point in his life.

Speaking of Tulip: I just have to say that the Storks’ co-lead is a fantastic character. She pulsates with such life and personality, a funny and quirky being who also shades a lot of complexity in her actions and her vocal performances – and in her animation. Tulip is a brilliant young girl who never is given her due: she invented (and fixed) a flying machine that doubled as a boat after a plane crash, and her rocket packs actually work before one of her test subjects take things too far. (You then want to question whether “Tulip’s help” really was the cause of the company’s low profit margins.) Let’s be blunt: there’s a clear, prescient feminist message here. A smart, capable woman whose ideas are dismissed, who can’t even be seen as a real person without the “orphan” qualifier? Really, there’s enough here that could fit an essay on its own. (This also ties into capitalism’s problematic approach within a social context, but again, that’s worthy of its own, separate critique.)

What we get here, through the overall tale told in Storks, is two young persons of different lives (and species, which winks towards its own idea of a diverse co-lead setup) who struggle with modern ideas of personhood and livelihood, all while engaging with the ultimate symbol of the classic “success” traditional ideal: the baby. And here is where things get interesting. Junior and Tulip fit within a particular archetype. A young couple, both of different worlds, who find themselves suddenly in the care of a child, neither of them ready to care of it, let alone care for themselves. They’re literally figuring it out all their own. In this way, Storks attempts to bridge traditional ideas of social success while questioning it all the same.

And, to be very clear, Storks isn’t a movie that’s going to delve heavily in such an idea. It’s silly, audaciously funny, with the kind of animated physicality that rivals Tex Avery for delightfully dumb cartoon exaggeration. The last CGI film to do something of this caliber is probably Madagascar 3 (one of mistakes of the Penguins of Madagascar movie was arguably to pull back from that gleeful embrace of cartoon exaggeration). Storks delights in its visual nonsense: its bird characters with hilariously perfect teeth; it’s fun, revealing montage of Tulip’s cast of imaginary workplace characters; it’s most sharpest creation in the form of a male wolf couple (wink) who fall in love with the baby and commands its pack into sheer physical recreations of bridges, mini vans, and submarines.

But those exaggerations do not (and should not) distract from its richer, well-considered points; they reflect millennial confusion and fears over how to approach a society that continually questions the nature of livelihood and family. Storks feels like a movie in which its creators almost lucked into devising a smartly considered world and a thematic heft that balances the film more than its previews indicated (and which hinders its third act a lot, which I’ll get to in a bit). In Tulip’s brief idea, suggesting the company they work for invest in a more diverse set of birds and animals, Storks sparkles with potential of a world in which its animals have as much life as its humans. It’s present in the wolves and the throwaway scene in which Toady interviews a bunch of animals. Storks enjoys the world it created and meta-commentary that flows from it.

This, in some ways, is also reflected in the scenes involving Nate Gardner and his family. Here, tradition again is questioned, if perhaps not as rigorously as it is with Tulip and Junior. It’s as cliche as it comes when we see two overworked parents consistently neglect their own kid, but at the very least, Nate thrives with a clear self-awareness of the situation, as in with the scene where he guilts his father to help him built the baby-catching contraptions on his house. Storks smartly doesn’t dismiss out of hand traditional ideas of success and family; it simply requests that its characters understand why it wants to achieve those goals, and be assured in that achievement. Note that Tulip and Junior do NOT fall dotingly in love with the baby and automatically become a family. The wolves’ are seen as in the wrong for this behavior, and so is Jasper, who realizes his ultimate mistake (falling in love with a baby just because its “cute”) and resolves to return to just finishing his job.

This is Junior’s ultimate lesson, which he recites (ironically, when he recontextualizes Cornerstore’s slogan into a personal mandate) when he finds himself in a factory filled with babies and an assortment of unemployed storks around him. This is also Storks’ weakest moment; its third act is lost in its perfunctory need to create an over-the-top climactic moment (if you watch carefully, Tulip and Junior don’t do anything but watch the chaos unfold in the entire sequence). A friend of mine commented on the need to kill off (and, for all intents and purposes, he is killed off) Hunter when he just wanted to protect his company, and he has a point. Turning Hunter, an antagonist who just had a strict corporate/capitalist mandate, into an out-and-out villain was a mistake, but you definitely get the sense that even the filmmakers felt ambivalent about it. (This more or less is notable in their approach to Toady, whose antagonism and motivations are hilariously, and purposely, unclear; Tulip and Junior barely grasp his role in the chaos that unfolded in the end).

Storks is infinitely more interested in the kind of silly, cartoonish world it created and the lost, confused characters who inhabit it, who open up to their insecurities through funny voices and dumb expressions, but whose insecurities are still present and significant. In its final moments, Storks showcases the myriad of families, and family types, who embrace their babies (many of whom could indeed never get babies the traditional way, something a “woke” sequel could really delve into?). It provides Tulip her rightful family, but more importantly, it gives her a sense of identity (family) and purpose (delivery of the baby). It also provides Junior a sense of purpose (embracing baby delivery at Cornerstore.com) as well as identity (Junior was never as lost in knowing who he was as Tulip was, but establishing a personal connection with her, and her family, does seem to provide him a level of peace he never knew he lacked). As heartwarming it was to see Tulip and Junior embraced by Tulip’s family, it was also right, perhaps even more so, to see the two of them nod at each other confidently in the workplace, confident in their new role.

Tip from Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh is the Young Black Female Lead We Need Right Now

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on August 24, 2016

Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh is based on the Dreamworks film Home, a buggered, incomplete piece of animation that never quite grasped the satirical edge needed to portray the abject and complete removal of citizens into makeshift suburban prisons. Home cared little about the uncomfortable connotation of such a premise, which resulted in a plot – in which a young black girl teams up with an alien outcast to try and find her mother – that could not shake off its racially-coded baggage. I know. I know. I wish I could just ignore the analogies – the wholesale removal of people from their homes, the wholesale removal of African people from their continent, the constant splintering of slave parents from their children to foster an economic system that possesses ramifications that last even till this day. But what you need to understand is that it is so, so hard, and Home did little to ease that discomfort from my mind.

In that regard, I had very few expectations of this show.

If a Home TV series had to be made, the best bet would be to ignore that entire premise and forge onward with new, unrelated storylines. Adventures of Tip and Oh does for the most part, although the occasional exploration of the Bov’s cinematic past actions is as awkward as you’d expect (more on that later). The animation is decent; the character designs are off-putting, as typical of Thurop Van Orman’s style, but functions well enough in movement, and viewers will find themselves getting used to it fairly quickly. The character choices are fairly trope-y and questionable, with Donny being a Mr. Krabs-esque non-entity, Sherzod gearing up to be the most decisive character in a while, and Lucy exhibiting a certain level of air-headedness that doesn’t seem to fit a single mother living in Chicago. These, and other creative decisions, suggest the writers are still working through some issues, but there is one thing that Netflix’s new show has right: Tip herself.

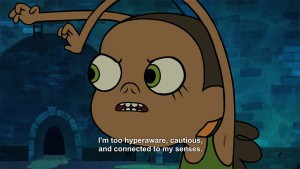

I didn’t warm up to Gratuity “Tip” Tucci at first. She seemed a bit all over the place. She is inconsistent, a bit aggressive, a bit loud, a bit too weird – especially compared to her cinematic counterpart. But then I realized something: that is the point. Tip is purposely, uniquely, her own girl. She is an eighth-grader who possesses her own very limited, very vain, very specific point of view. Her aggressiveness, loudness, and weirdness is uniquely her own. The writing doesn’t quite do her any favors, specifically in terms of the situations that she finds herself (and Oh) in. But Tip herself is special. She is unabashedly herself, not particularly concerned to fit within the parameters of young girl character templates – specifically, young black girl characters – that came before her. She is Penny Pride – clever, determined, confident to a fault – mixed with Star Butterfly – extroverted, adventurous, out-of-her-league. Tip is confused, lost, conceited, goofy, and, yes, even grating. She is all those things – which makes her the best, most important young black female lead for children today.

I need to reiterate something: other than Doc McStuffins – a show for preschoolers – we do not have a single animated show on the air with a black girl as a lead. Mostly cartoons are driven by young boys (or talking animals). There are more shows now with girls as leads, and/or shows with strong feminine characters. But they’re mostly all white (save for Steven Universe’s Garnet, which is another matter entirely). And that is fine. But in this era and in the call for more diversity, it’s telling that, as usual, young black girls are continually, routinely ignored. (Full disclosure: I pitched this piece to a well-known site, which was rejected, and which I deeply believe contributes to this problem.) Seeing and experiencing someone like Tip on my screen felt revelatory. It made me realize how limited in scope my expectations of what young black girls could be. (Note I didn’t say “what black girls should be,” which is an extremely important distinction.) I love Tip because, sometimes, I don’t love Tip. I love that she’s sweet and loving and naive and annoying and too much and quirky and super-weird and sometimes “uppity.” Black girls need to see this. We all need to see this.

This scene epitomizes the kind of person Tip is as a character. There’s no contextual reason why she sniffs herself (they’re in a sewer, but there’s no reason why she sniffs her armpit versus any other part of her body), but it shows her her spirit, vanity, and goofiness all in one brief monologue.

Tip isn’t African-American. She’s Caribbean-American. Her grandparents immigrated from Barbados; Tip is second-generation. The show doesn’t play around too much with this, although it is nice to see when they do. (I would love to see more Barbados-inspired bits on occasion, in the fun ways that Sanjay & Craig sometimes played with its Indian-related bits.) I don’t expect the show to really do that, though, mainly because the writers don’t seem to really grasp the full relevancy of what they have in a character like Tip. There’s theoretically a lot to unpack in a show in which the Bov implemented forced displacement and occupancy, where the setting is Chicago, and where Tip and Lucy live by themselves sans a father figure. When Tip’s grandparents visit in “Wrinkly Humans People,” that awkwardness is palpable, but the writers don’t see it. After all, her grandparents deeply distrust the Bov for what they did, and you honestly can’t blame them. Yet the show works it so as to suggest that it’s her grandparents that are in the wrong, that they’re the ones who are, essentially, the bigots, since they just can’t get over what the Bov did. Well, of course they can’t. History is ugly.

Even still, there is potential here. There is a rich complexity in the idea of Tip’s broader acceptance of the Bov and, specifically, Oh, and how that comes up against the reality of what the Bov did. There is perhaps something to how easily a young Tip has forgiven the Bov in order to maintain the stability of her small family unit, and how that continues to push up against those still harboring resentment towards their occupiers-turned-neighbors. It would be deeply interesting to see episodes in which Tip has to, in some way, address how she justifies her love for Oh, as opposed to her past hatred for the Bov’s role in separating her from her mother. Adventures with Tip and Oh might have been better served ignoring all that overall, but although I do applaud the show for dipping its toe into the thornier sides of the film, I doubt the writers have the temperament to hit such dramatic notes.

That’s a dramatic layer way out of reach for this crew. At this point, in its first season, it would be just enough to take a fun, deep look at Tip herself (in the context of a young black eighth-grader with only a mother living in Chicago). As a unique character, the writers provide her with the variety of traits that I’ve mentioned earlier. As a character who will be developed, that where the writers fall short. It’s tricky, because the show doesn’t need to be an in-depth (if silly) examination on what it means to be a young black girl in Chicago – aliens or not. But it would be worth exploring some of the issues unique to that worldview and experience. The clearest example of this dilemma lies in “Angerdome,” an episode in which Tip deals with her anger. There are volumes of content that could be written that explores the social exploitation and discrimination that exists within the “angry black woman” trope. It is both vicious (which posits all black women as unstable and prone to violence) and commodified (from the lighter-but-overused “sassy” trope, to pushing their angry reactions on reality TV). It’s hard to say how the writers see all of this in “Angerdome,” though. There’s a moment, after various characters tell Tip to calm down, where she proclaims, “I’m allowed to be angry!” and it is wonderful; filled with the personal, determined, defiant spirit that young black girls need to hear. Yet the power of that statement is undercut when, immediately after, Tip resigns to needing help (and an outlet) to deal with her anger.

That’s what makes it hard. There is the real, distinctive lesson which allows kids to understand that having an outlet to deal with anger is important, and I can’t fault the show for dealing with that (although the answer they come up with is muddled). At the same time, the show mostly ignored the opportunity to explore Tip’s individual struggle with what it means to be a black girl who gets, and is allowed to be, angry. It’s a powerful statement that the writers fail to notice as a powerful statement. It’s part of the overall verve of the show, really. It’s great to see Adventures with Tip and Oh use a character like Tip to have fun with the general complexities of childhood, especially within such a specific premise. It’s tougher to see this done separate from the unique characteristics and history that Tip (and the show) embodies: the black, only-child, fatherless, Chicagoan setting. The universal ideas are fun, and pushing them through Tip is wonderful, but the writers have an opportunity to really explore Tip’s experiences at a personal, raw level, and I don’t think the writers see it – or they refuse to.

Still, I praise the fact that a character like Tip exists. She is simultaneously fun and frustrating, and it makes her necessary to see a character like her on television. What ever issues or concerns that may happen around the lives of the Tuccis (which, for all we know, could be fixed by season two), Tip’s goofy, abject, unforgiving weirdness and quirkiness – so often contributed to white women to the point of a dated, oft-misunderstood trope – has been finally applied to a young black girl. It’s just good, refreshing even, to see a black girl outside of a typical “no-nonsense” role. (Tip is no-nonsense, but it’s defined within her weirdness, not as a sole contrast to those “silly” white kids.) A lot of her appeal is due to the voice artist, Rachel Crow, a 2011 X-Factor contender taking the role from Rihanna from the movie. Rihanna had gumption, but at best her voice work was merely passable. Crow brings a serious, specific attitude to Tip – a rough energy that’s wonderfully infectious (in the same multi-layered cadences that the late Christine Cavanaugh gave to Gosalyn Mallard). She also has a distinct singing voice that manages to add flavor to both the show and the character, without it being too distracting or random.

So flaws and all, I look forward to see where Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh takes Oh and Tip in future stories. The creative critic in me wants to see the show lean a little harder on its premise, on its boundaries and issues, just to see them contextualize how Tip might respond to those tougher dilemmas and grow as a person. I would love to see those issues hit upon, to expose it to kids, particularly young black girls, who struggle through those issues every day. As for now though, I just want to see more Tip. I want to see more of her odd, assertive, annoying behavior. I want to be challenged, bothered, and amused by Tip’s antics, because I want young black girls – and all viewers, really – to understand that being like Tip is okay.

(Final note: I know this is “just a cartoon.” I know I should just enjoy it for what it is. What I’m telling you is, I just can’t. Not with what I know and experienced, not with what I’ve read, not with the history and context of this country and even Chicago itself inside my head, not with the news stories and the personal accounts of people’s experiences shared every single day. I physically, emotionally, psychological cannot separate the two. I can only channel it, and I would hope and love to see Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh do this as well.)

Raising Adults to Children: How Animated Adults Became Man-Children

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on September 29, 2014

I wanted to do a piece about kids networks and recent rash of man-children cartoons for a while now – by which I mean, cartoons staring mostly adult-ish characters who have simplistic pleasures and seem more prone to skirt responsibilities in order to engage in juvenile behavior or activities. In some ways, the “man-child” has always been part of the animated landscape – Bullwinkle J. Moose is a fairly classic man-child – but it was tempered with a sense that the character, at least at some level, had a clear direction, an idea that he was doing something right, a guiding voice (in this case, Rocky), and a sense of logic that drove his actions. Bullwinkle was goofy, sure, but he was a loveable goof, loyal and passionate and at least somewhat-down-to-earth. Jay Ward’s titular cartoon was also loose and free with its characters, easily plopped into simple plots that doubled as smart-ass satire against current events. Other cartoons, too, emphasized semi-silly characters who were at least dedicated to their jobs – Super Chicken, Roger Ramjet, Dudley Do-Right.

AO Scott wrote this pretty interesting piece about the fall of adulthood recently, and while it’s a little rambling, it made me think about current cartoons today, particularly on Nickelodeon, and their emphasis on man-children adult characters. After all, Nick’s call for animation pitches only allowed for ‘toons with kids or man-children adult protagonists (mainly due to their research stating that kids today just want comedy). There’s really nothing inherently bad about the man-child adult icon, but the recent batch of cartoons with such characters helming the show are dialed up to eleven. These are not characters who enjoy their childish pleasures while working their way through their (often newly-earned) responsibilities. These are characters who thrive in their juvenile behavior, behavior that is encouraged and often ends up saving the day despite the fact that such behavior would be dangerous and/or illegal. This can only go so far before the true nature of growing up becomes muddled.

To clarify, the rise of man-child entertainment arose from three specific events: 1) the social embrace of “nerd” culture – things like comic books and cartoons, media originally created for kids, 2) the recession, which leaves the younger generation aloof from job/domestic responsibilities due to the difficulty and ambiguity of acquiring them, and 3) what can be described as the “new sincerity,” which in some ways arose from “ironic culture.” [The best way to describe this would be to think about someone who enjoys something objectively terrible because of its terribleness like The Room, or Saved by the Bell; if there’s a certain self-awareness about liking something terrible, it’s ironic, but if there’s a fondness for that terribleness, its sincere. The line between the two is obviously muddled, but a lot of that tends to cleared up by how much interest in paid into the creation of the entertainment in question – the actors, the crew, the producers, the networks/studios, and so on. Liking The Mighty Ducks might be ironic if you laugh at its awfulness, but it may be sincere if you immerse yourself in Mighty Ducks lore, discuss the writing of David Wise, talk with animators about their time on the show, etc.]

Part of the appeal of the man-child (and a lot of the aspects of Scott’s piece, particularly with his sections on Beyonce and Taylor Swift) is the emphasis of the individual’s stake in his enjoyment. Pushing against the social tract that tended to instill adulthood at one’s mid-20s, which included marriage, kids, a home, a job, a car, and “most importantly,” the dismissal of all forms of children-marketed entertainment, man-children (and their female counterparts) thrive and proudly embrace their love of such pleasures, like video games, comics, cartoons, and young adult books. These are people who absolutely believe they can take care of their responsibilities along with loving what they love, even if such responsibilities will have to occur months or years later. And let’s be clear: these people are one hundred percent right, but there is an asterisk, as that passion can be all-consuming. Criticisms against such behavior and/or the juvenile media tend to come off as a personal attack, which can explain things like more aggressive sides of gamergate, the MLP fandom, and lovers of Harry Potter, Twilight, and The Hunger Games.

Life’s always been about the balance between one’s responsibilities, particularly the ones associated with adulthood, and pleasures, although back in the day, the pleasures were always of the “adult-ish” kind: fishing, vacationing, playing a sport, reading. There was a distinct line between the two, too – there was a time for work, and there was a time for play. Blurring the line was a strict no-no. Ducktales and TaleSpin, for example, were clear to make this distinction. Scrooge McDuck was absolutely serious about his pursuit for business and financial deals; his pleasure, ironic enough, came from literally dipping into the money he earned. Scrooge has always been an “adult” in that way, and any sense of his business acumen as a symbol of being uptight and suppressed was rare. In only a few instances was his “greed” portrayed as a real issue for the character, and that greed was always set in some “character-removed” manner. In the “Treasure of the Golden Suns” saga, the greed was only a problem when he became fully afflicted with gold fever. Additionally, it’s in this five-part pilot that he gains a real family, the “other” mark of adulthood, emphasized later in “Once Upon a Dime.” Everything about Ducktales was built around characters being and embracing adulthood, and the insanity culled from it.

With TaleSpin, Disney is directly tackling the man-child idea, delineating the idea that pleasures are okay but only up to a point. Going beyond that point is more trouble than its worth, or prone to cause trouble. Baloo is a safe man-child, a lazy, baffoonish bear who thrives solely in his skills as a pilot. His juvenile behavior often masks his crippling insecurity, pushing him to levels of petty ridiculousness, like his conflict with Ace London in “Mach One for the Gipper,” or Louie in “For a Fuel Dollars More,” or even Becky in “The Bigger They Are, the Louder They Oink.” Yet that push also drives him to be level-headed at times and even heroic, like when he called out Becky’s reckless business behavior in “A Touch of Glass” or when he went up against Don Karnage’s laser gun in the pilot. TaleSpin shows often that while there’s a certain value to Baloo’s goofball antics (like in “My Fair Baloo,” where, it should be noted, that the goofball antics are tied directly to hands-on, working class intuitiveness), that there is a limit. When things go too far, things go bad; it’s only when you act like an adult do things fall in line. (Becky learns this lesson in a most serious way in “Her Chance to Dream,” dismissing the pleasure of leaving the stress of life behind in order to stay and raise her daughter).

The Disney Afternoon was emphatic on adults cartoon characters needing to act like adults, comic or cartoony-slant be damned. Gummi Bears was marred in the need to care for Gummi Glen. Darkwing Duck’s more ridiculous pursuits were tampered by his need to take care of his daughter (and his struggles with his girlfriend). Rescue Rangers overall was about its characters coming to terms with various degrees of adulthood – Monterey Jack tackled his addiction, Gadget confronted her insecurities multiple times, Chip often dealt with his role as a leader. Dale might seem the exception, but the show, like TaleSpin, delineates Dale’s behavior. When he goes too far, things go bad (and likewise with Chip, when his practical jokes go too far in “One-Upsman-Chip”). The show makes it clear that Dale’s childishness is necessary in the sense that its unpredictability gives the team an edge, and when it comes down to it, Dale indeed will pull up his metaphorical pants and get to work. (In truth, it probably wasn’t until Donald in Quack Pack did the Disney Afternoon push against the role of adulthood. Goof Troop and Bonkers, despite their problems, emphasized its characters attempting to be responsible grown-ups.)

Adult characters in cartoons were simply adults, flawed and broken of course, but not so much as the crazy world around them. Rocko’s Modern Life was perhaps the clearest example of this, the show about a young adult just simply trying to run his life, notably away from his parents way back in Australia. It’s the world that’s insane, not the character, and the comedy was in watching Rocko try to do simple, mundane, adult things, like the laundry or going to the beach or getting to work on time. Hefer, Rocko’s friend, is definitive the show’s man-child, and at no point does the show suggest that Hefer’s behavior is warranted or ideal. The show’s clearest direction of adulthood, oddly enough, is created through Philbert, the one who literally has to go on a pilgrimage to become “a dolt” (note the play on words here), and he’s the one who ends up getting married. Rocko gets a lot of discussion over the various ways it got away with adult gags, but it’s ironic that a show known for its juvenile gags masks its emphasis on maturity and growth.

Somewhere along the lines, the cartoon philosophy changed, and we can’t quite place the blame on Nickelodeon. CN brought us Johnny Bravo, starring a character epitomizing the worst of the man-child, a walking Dane Cook-esque “bro-seph” who only loves himself and treats women terribly. The show, of course, makes it clear that Bravo’s behavior is absolutely abhorrent, that his sexist actions result in him put through physical pain. Yet Johnny has no job and no prospects, and he lives with his mother (more or less), emphasizing his separation from adulthood. We are meant to laugh at Johnny and in no way look up to him.

Then there’s Spongebob Squarepants. I mean, it’s easy to just call this show as the catalyst for the man-child adult run in animation today, but Spongebob is a curious case. At least prior to the movie, Spongebob relished in his pleasures, such as blowing bubbles, jellyfishing, and karate, all of which are representative of his immaturity (in addition to his complete inability to get a boating license). However, Spongebob owns his own home and he works at a job that he not only loves but he’s actively good at. Spongebob engages in the things he enjoys, but even he knows when things go too far, and he always keeps his job (and taking care of Gary) first.

I think Nickelodeon took the wrong information from show’s popularity. Instead of observing the various components that made the show function so well – in that a character who enjoys his pleasures also is relatively dependable, to a fault – they saw “man-child adult” and doubled down on it. This in some ways explain Spongebob’s current failings – the character is a lot more irresponsible, dangerous, and stupid, like marrying Krabby Patties, and it also explains Nick’s current off-putting shows, like TUFF Puppy and Breadwinners.

The titular lead in TUFF Puppy, in contrast to Johnny Bravo, is supposed to be admired, I think. We’re supposed to laugh at Dudley similarly to how we laugh at Johnny, but while Johnny’s behavior leads to bad, comical scenarios, Dudley’s behavior is, at worst, a comic distraction, and, at best, heroic. The similarities are uncanny – both live with their moms, both are moronic to a fault, both wear black shirts – but while Johnny falls flat on his face, Dudley is rewarded with a new job, friends who tolerate (and accept) him, and amazing ass-kicking abilities. (Note how Johnny’s martial arts are a joke, hyperbolic posturing, while Dudley’s nonsensical movesets can handle all sorts of criminals). In a way, Dudley is more akin to Rescue Rangers’ Dale, but Dale, as mentioned, is distinctly tempered. Dudley, meanwhile, is free to go overboard, and the show goes along with him, with its criminals and fellow agents free to go ridiculous as well, consequences be damned. I’d argue that there was a minor attempt in the first season to bring some sort of pathos to its man-children setup, with the show attempting to establish strong if goofy relationships between Dudley and characters like Kitty, the Chief, and his mother. That pretense was dropped quickly, turning all the characters (even Kitty) into unrepentant goofballs. TUFF isn’t so much a crime fighting agency as an unsupervised playground; the show isn’t so much about balancing work and pleasure as its about unrestrained comic inanity.

Breadwinners, likewise, portrays its workplace and its workers as instruments of chaos. To Buhdeuce and SwaySway, delivering bread isn’t just a job they enjoy but a massive game to them, an endeavor that allows them to be wildly goofy and destructive sans consequences. Breadwinners has a slightly better handle on its character relationships – the strong bond between the main characters; the easy-going connection with their mechanic, Ketta; the tense relationship with the antagonist cop Rambamboo – but again, it’s all a means to an end, excuses to have its characters engage in juvenile behavior within (ostensibly) a working environment. There’s no meaning to their role as breadwinners other than it’s vaguely important, and, like Dudley, their chaotic behavior often saves the day more so than it ruins it. Notably, both Breadwinners and TUFF Puppy can’t define their workplaces or relationships with any clear-cut boundaries, since that would break the protagonists’ hold on their childish behavior. In other words, these are characters who can essentially do whatever they want; forces that try to tamper that down just don’t get it, despite such dangerous behavior. No one even questions it.

It’s sort of why the 7D never feels like it’s getting off the ground. Like TUFF Puppy and Breadwinners, 7D seems primarily concerned with its workplaces and relationships as excuses for its characters to be comically nonsensical. There’s little hint that the dwarfs’ mining or the queen’s ruling is other than a means for hilarious stuff to happen. And, like Kitty and Rambamboo, 7D’s Starchbottom (note the name) is the show’s stick in the mud, since he’s the only one who takes his job with any sort of seriousness. Locales and relationships, again, are ill-defined, since that would interfere with the joke-telling. Grim and Hildy, the show’s antagonists, are married, but there’s no sense that the marriage is anything beyond the comic scolding of Hildy’s aggressiveness to Grim’s submissive stupidity. In 7D, TUFF Puppy, and Breadwinners, (wo)man-children rule, with nary a thought.

There are two holdouts to this questionable trend. My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, for its faults, is refreshing, since its six main characters have real, adult-ish roles and pursuits (even Pinkie-Pie, who pursues her childish passion for partying with an adult-level fervor). The world of Equestria is chaotic, but there are rules and limits, and the characters are forced to pay attention to those limits to thrive. Kung Fu Panda: Legends of Awesomeness is wildly flawed too, but at its best, it strikes the right balance between Po’s love of childish things and the need to engage in responsibility. It does struggle with this at times, but it does showcase Po’s childishness within a “work” environment as problematic, not rewarding.

I’m ending this this piece by mentioning Wander Over Yonder, which is quite analogous to Rocky & Bullwinkle – a childish “adult” (Wander) who is guided by a more mature figure (Sylvia). Both shows are loose enough allow their man-children characters to behave chaotically unchecked, but, like its forebear, the show is loose enough to plop its characters in random scenarios to let the comic behavior breathe, and the episodes balance the sillier stuff within its own brand of satire (“The Hero,” “The Troll”), and again, it’s clear when Wander’s behavior goes too far or is portrayed as dangerous (“The Void,” “The Box”). Here, man-child behavior is celebrated but is distinctly curbed – there’s a time and place for it. That’s really the issue in a nutshell: the best shows embrace the enjoyment of adult characters and their “toys,” yet understand that there’s a time to put them away. THAT’S the lesson I fear is being lost.