Posts Tagged Comics

Tumblr Tuesday – 04/15/14

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Childhood Revisited, Television, Video Games, Writing on April 15, 2014

Tumblr has been slow the past couple of weeks, but I managed to gather a few nifty ones for this week’s Tumblr Tuesday:

— Some observations on an episode of Darkwing Duck

— My own quick and dirty observations on the #CancelColbert nonsense

— A hilarious bit starring Steve Coogan

— Someone compared Parks & Recreation characters to Animal Crossing characters and it’s spot-on

— Someone else is schooled when misguided tumblr activism is applied to The Legend of Korra

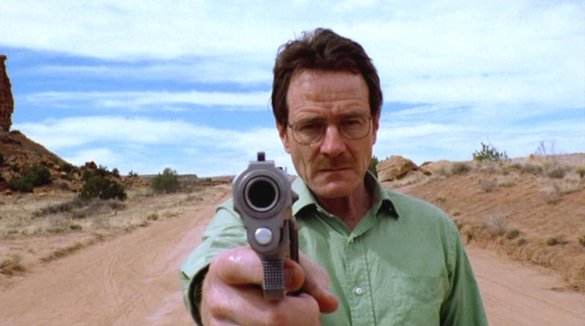

Breaking Bad, Arthur Miller, and the New American Tragedy

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Comics, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on October 2, 2013

It was in “To’hajiilee” when it all clicked. For me, anyway. Walter White had just just been handcuffed, finally, after so many months of his infamy and actions wrecking havoc not just in Albuquerque, but pretty much all over the Southwest. He is brought face-to-face with Jesse Pinkman, the kid who just played the manipulation game like the adults around him, and managed to win. He stares at Jessie and calls him a “coward.” How does Jesse respond? He spits in Walt’s face. The two immediately starts to rough each other up much as they can while Hank and Gomez barely restrain them. The final season of AMC’s titular show has been about many things, but in particular about how lies, deceit, paranoia, and manipulation can be, and will be, exposed, and the full, painful consequences of these revelations. The sad truth is that it ends up being pure violence, as distinctly portrayed in those horrifying final five minutes before the episode cut to black. You can’t lie around a punch in the face or a massive shootout.

That mini dust-up, though, reminded me of a moment in Arthur Miller’s tragic American play, A View from the Bridge. It was the spit in particular, for in the play, a confused and desperate Eddie Carbone, genuinely concerned for the well-being of his daughter (but deep down, more concerned about his sense of masculinity), calls immigration to stop his daughter from marrying the “dancing European” Rodolpho, an act of betrayal that enrages Marco, Rodolpho’s brother and protector. In a tense scene, Marco spits into Eddie’s face, and the two indeed have their own mini dust-up before being restrained. Breaking Bad’s little desert fight reminded me perfectly of that scene in A View, and while there are plenty of cinematic fights begun over a loogie, Breaking Bad connection to Arthur Miller’s seminal work struck a chord. In fact, Breaking Bad connects to the general output of Miller’s work, marking Vince Gilligan the new, definitive author of the new American Tragedy.

Of the many themes one can draw from Miller’s plays, the most common and important one was about the power and meaning of “the name,” which, to put simply, represents an individual’s reputation. In The Crucible, John Proctor signs his name to confess to a false accusation, then goes against it when his defiled name would be put on the church for all to see. In Death of a Salesman, Willy Loman desperately tries to get his disillusioned son to pursue a real business, a legacy he can leave behind that means something, unknowingly being the cause of Biff’s unfocused drifting in the first place. He kills himself to jumpstart his son’s call to action, for god’s sake. In the final climactic scene in A View from the Bridge, Eddie bellows out to Marco to restore his name after his own act of betrayal destroys it in front of his friends, family and community. Eddie will be damned if his name is sullied, and even fights Marco to his own tragic death over this.

Sounds familiar? Did Walt read A View from the Bridge and somehow take the story to heart? “Remember my name,” “I am the one who knocks,” “Tread lightly” – these are the words of a man who knows what the name Heisenberg means, and who rushes in with a metaphorical knife to ensure there are no Marcos around to sully it. Hell, a desperate Walt shoots Mike over a series of mild insults – he’ll be damned if anyone, even someone like Mike, would question the reputation of Heisenberg.

There’s been a lot of critical speculation that Walt has always been Heisenberg, that all Breaking Bad’s early episodic claims of leaving enough money for his family when he’s gone was a lot of postulating, masking a monster beneath that’s always been there. I used to agree with this – but in pondering this argument, this connection to Miller’s American Tragedies, I now have my doubts. Tragedies are at their most poignant when the protagonist, for all intents and purposes, means well despite his horrific actions. He has a moral/ethical endgoal, but forges a decidedly immoral and unethical (or at least questionable) path to get there. If Walt was always just a burgeoning, evil monster, who just needed meth to unleash it, there would be no tragedy.

Classic Tragedy made it a point to show the protagonist realize his horrific mistake and suffer for it, the cathartic release of problematic behavior come to light – Oedipus, Agamemnon, Romeo and Juliet. American tragedy had no such reservation: protagonists stubbornly stood their ground in their decisions, and while acknowledging and stewing in own their regret, ultimately gave into their sins. John Proctor went to the gallows. Eddie, no short of irony, is stabbed to death with his own knife. Willy Loman blindly rants and raves to his own vehicular suicide. These are not people who truly realized their mistake and simply suffered for it. They went to the grave aware of their offenses but steadfast in their in defiant denial to change. Gilligan, among his showrunner entourage of Weiner, Sutter, and Chase, introduced the world to the New American Tragedy focused on men who not only thrive in their monstrous behavior but fight tooth and nail to maintain their success, giving false or little concern to those who crash and burn along side of them. It is tragic in that these people, who have “everything,” or, at the very least, are provided very obvious means to achieve anything, but opt to grab hold onto a Devil’s contract and profit within its cruel legalese.

To be clear, Walt is a New American Tragic hero, in so much that a murderous, meth-creating, drug dealing, anti-hero can be. It’s why so many people “feel” for Walt (and uncomfortably focus their rage at Skyler) – the New American Tragedy isn’t really about people that mean well. It involves people who are flawed, exaggeratedly so, in incredible, monstrous ways, yet nonetheless have a clear sense of direction. Drama has gotten as “larger than life” as comedy has, and if Community, It’s Always Sunny, and Venture Brothers go to great lengths to make its comedy stick, drama can, too. So Walter White can blow up meth gangs and beat cancer and make powerful electromagnets, bitch, and every choice is over the top and every coincidence is wildly outlandish, but the show focused primarily on one character against the world using his intelligence, spurred on by an enormous ego and an incredible amount of luck, to beat it back. Walt, like Dexter from Dexter or Tony from The Sopranos or Don from Mad Men, are awful people who decisions are made to be understood, and they are decisions that managed to work, even if the results of these decisions are pure evil. “Rooting” for these characters is meaningless in this New American Tragedy. Instead, it is about people who will go through anything to make their ideals come true and keep their legacies intact, and knowing that it will never last and will violently bring down anyone crazy enough to willingly (or unwillingly) be the vicinity. We as an audience can only watch the inevitable happen. The American Tragedy always had an air that maybe, just maybe, the protagonist can escape, or at the very lease, understand his fate. The new New American Tragedy says no – the protagonist will go down in flames, and you can only sit back and watch.

“Ozymandias” is a poem by Percy Bysshe Shelley about the inevitable fall of all leaders. Ozymandias (not coincidentally) is also the name of a brilliant “superhero” in Alan Moore’s Watchmen, a genius millionaire who “masks” his true intentions, unleashing a massive-scaled, unexplainable tragedy that destroys New York, in order to bring the world together and prevent a nuclear war. That horrific event will be made even more tragic when, in the final panel, a lazy reporter pulls out Rorschach’s notebook that reveals Ozymandias’ plan to a T. And so it goes that the episode entitled “Ozymandias” is not only about Walt’s almost-instant “fall from grace,” it’s also about how Walt’s efforts inevitably lead to their own insular tragedies – Hank’s death, Walt’s loss of money and empire, Walt Jr.’s exposure to the truth, Holly’s kidnapping, the utter destruction of the family, Walt’s phone call and “cathartic” confession to it. With two episodes left, Walt’s disappearance into hiding, after he stated he had unfinished business, is the Rorschach notebook, a quiet, unassuming reveal that will lead to even more chaos (that may involves an assault rifle).

“Granite State” built upon “Ozymandis,” tracking Walt through every trick in his arsenal to exact his revenge, and failing. He can’t get hitmen, he’s tossed out in the middle of nowhere, he can’t get Robert Forester’s “fixer” to stay two hours, even for extra money, and he can’t use the claim for family as Walt Jr. throws that excuse right into his face. The name-theme is particularly noticeable here, and how it’s reduced to nothing. Walt has to change his identity completely, reducing “Walter White” to a sad, skinny man dying in bed, and “Heisenberg” to a scared man afraid to walk eight miles in the snow. Skyler changed her last name, cutting off all ties instantly. The sympathy established for this monster is built in the utter destruction of the name (and not necessarily because he’s up again a gang of sociopaths worse then him – these are guys who pretty much did everything Walt did, just more up front and without the false sense of regret) and all it meant. It meant terrible, terrible things, but it meant SOMETHING. So as we watch Walt seethe, watching his name ripped to shreds by Gretchen and Elliott, metaphorically spat upon in every way possible (the Charlie Rose interview destroys all of them – Walter, White, Heisenberg, Grey Matter, the blue meth signature), I can see Eddie Carbone in his face, demanding Marco to give him back his name. That’s all he has, and even the most evil of men can garner sympathy with this claim.

And so it goes in “Felina,” the low-key, somewhat divisive, but perfect ending to this New American Tragedy, where Walt comes to terms with himself, and we as an audience indeed finally reach our cathartic moment. Right at the beginning, as Walt struggles to start the car in the cold, lonely, isolated world of New Hampshire, he closes his eyes and pleads to a higher power just for a chance to get home. The results are that the car keys fall right into his lap. It was in this final act – of forcing Gretchen and Elliott to create a trust fund for Walt Jr., of acknowledging his outsized ego as the real motivation for his heinous actions, of taking out the Neo-Nazi thugs and freeing Jesse from his prison – that he came to the realize who he was, what he meant, and what truly he needs to leave behind. His money is left to his family but not in his name. He watches his literal namesake, Walt Jr., enter the apartment, gone from his life forever. He takes out the Neo-Nazis with nary a mention of the Heisenberg reckoning.

I loved how utterly workman-like this episode was, Walt robotically going through his final actions without the blunder and bluster of his lies and manipulations threatening to unravel like before. It’s pure Walt, no longer masked by any false distinctions. When he and Jesse stare down each other, the latter with a gun in his hand, I’m reminded of Biff’s final confrontation with Willy, who too was close to death via a rubber hose. Walt, shot in the stomach like Eddie’s stab to the gut, spends his final moments wandering around the catalyst to his infamous name: the meth lab. There was a chance to escape his fate – staying in NH – and there are still terrible, terrible consequences – his family is ruined, Hank is dead, Jesse is scared for life – but similar Eddie, John, and Willy, Walt is a victim of his self-created tragic fate. They all confronted who they really were and what they really did, and ultimately died for it. Yet while Miller let his protagonists face their regrets and become self-deluded martyrs, Walt embraced his monstrosity and let it consume him, yet managing to focus his terror through a minor mission of redemption before succumbing to his grave.

Arthur Miller’s plays were fascinated with the perversity and corrupt fallacy of the American dream, focused not on broad ideas but on personal stories. Fathers and father-like figures, weakened and crumbled by their own personal flaws, which inadvertently are exposed, ripped apart, and inevitably lead to a vicious downfall. Miller was brutal, with implied hangings in The Crucible and brutal choreographed fights in A View, but he’s not Vince Gilligan, and it’s not 2013 TV. If he was, though, I could see Miller fitting perfectly in the Breaking Bad writing room and weaving another chapter of the downfall of Walter White. Breaking Bad brought forth a new idea of tragedy, a New American Tragedy, so expansive and far-reaching and horrific and personal. These last four episodes made it clear. Like Miller’s tragedies sought to beat back the idealized 1950s of Americana, Gilligan signature work destroyed the 2000s idea of definitive entitled Americana. I was happy to be there throughout it all.

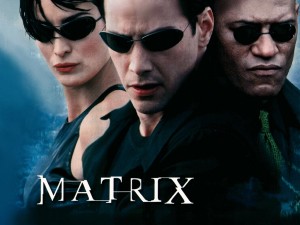

What is The Matrix? The Beginning of the Bloated Franchise

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Film, Television, Uncategorized, Webtoon, Writing on September 11, 2013

The casting of Ben Affleck as Batman in the soon-to-be-teased-relentlessly Batman/Superman film caused quite the stir among the internet, filled with spiteful Twitter comments, rage-filled Facebook posts, and lists-among-lists of why he’d be both great and terrible. Of course, this kind of massive knee-jerk response is nothing new, since there was a tremendous amount of it when Heath Leather was cast as The Joker, or when Michael Bay announced his take on the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Riling up the fanbase has become in itself a new form of marketing, whether in positive forms (which is the key to Comic-Con’s specifically-designed trailers and teasers and… amusement rides), or negatively, which one could say is what propelled a giant portion of controversy over Man of Steel and World War Z. There’s no such thing as bad publicity, and to studios, all they really care about is that sweet, sweet green.

I wanted to take a step back, though, and look at where we are now. Watching this geek-based reaction from a distance, it’s rather crazy if you think about it. This kind of response would have been completely unheard of back in the 90s – hell, even in early 2000s, this egregious “stirring of the pot” would have been nigh impossible to do. Tracking this kind of response backward yields some interesting results – through Batman Begins, Iron Man, the entire Marvel film universe, Scott Pilgrim, Indiana Jones and the Crystal Skull, Harry Potter and Twilight, just to name a few. Sure, the emphasis of “the franchise” has become the raison d’etat of Hollywood nowadays, especially since overseas is now where the real money is (resulting in sequels to films that hardly deserved them – there’s a third Chronicles of Riddick, despite the second one completely bombing). The question is, where did this out-of-control bloated behemoth stem from? Oddly enough, it all began with one film that indeed tried to spread across all these entertainment platforms, and failed. In its ashes was born this blockbuster monster of cinematic proportion that is now creeping into television, video games, comic books, and animation. Enter The Matrix.

——————–

It seems so far ago, but when The Matrix was released way back in 1999, it was essentially The Pirates of the Caribbean of its time: a pleasant surprise that no one was expecting. Sci-fi films were still relatively niche and most of them that were released in the late 90s were terrible, just like any other pirate film that entered the cinematic landscape. But here was The Matrix, its tinted green cinematography overlaying audaciously new (at least in America), gravity-defying fight choreography, all couched in the basic question of what is reality, which seemed particularly relevant in the rise of what the internet and virtual reality were soon to become. The Matrix was an eye-opener, and while I personally was somewhat lukewarm to it when I first saw it (I warmed up to it more on subsequent viewings, but I’m still not what you would call a fan), I can’t help but acknowledge the power it held, especially within the geek community, which at the time still was a forgettable market to Hollywood. Fansites exploded across the internet, and people, for a long, long time, cosplayed in their black trenchcoats and sunglasses as they went to see the film over and over.

No one knew it at the time, but this was the beginning.

The Matrix nabbed over $450 million by the time the film ended its theatrical run. That cashflow began all the talk and speculations of a sequel, which is normal for any winning film, but the Wachowski’s want to do something insane – make TWO sequels. The “trilogy” concept more or less died out with Indiana Jones, and the only thing that was considered worthy of it was the Star Wars prequels, and we all know how well that turned out. The same sentiment, of course, could be said of Reloaded and Revolutions, and both franchises showcased how the money-making bloat of the summer film franchise could overcome both critical AND public conception. But unlike Star Wars, which was always (and will always be) an unstoppable franchise force, The Matrix was new, and while the first film was proven hit, the question of whether it was franchise worthy was something else entirely.

The Wachowskis, of course, sold us all a bill of goods. And it’s not as if The Matrix didn’t have enough content to sustain a number of new, interesting, and intriguing stories within its premise. With all their claims of possessing numerous stories to tell, it’s extremely surprising that Reloaded and Revolutions were what we got. In addition to all that, though, were ideas that slipped its way into different media – anime (The Animatrix), video games (Enter The Matrix, The Matrix Online, and The Matrix: The Path of Neo), and comics (The Matrix Comics). The Matrix franchise was trying its damnedest to worm its way into the pop culture conscious just like Star Wars did so many years ago. But there was a glaring problem: the sequels kinda sucked, about half of The Animatrix animes were in any way decent, the games were broken and not very good, and comic culture wasn’t prevalent enough to warrant enough a large readership for the comics themselves.

The problems with Reloaded and Revolutions were twofold, narratively and thematically – they took focus away from the cool (and much more interesting) parts, the Matrix itself, and focused on Zion, the “real world,” which the writers failed to mine for anything worthwhile. Secondly, they turned the philosophical questions of reality and instead asked religious ones, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing per se, but again, the Wachowski brothers weren’t half-assed to be nuanced, and when they were, it was nonsensical. The games, the comics, and anime were supposed to answer all the lingering questions – but 1) the internet had yet to become so interconnected to the various media forms, so many people barely bothered with that, 2) the films themselves were so problematic that few people actually cared, and 3) those that did were only left with MORE questions. (In some ways, this is what doomed Tron: Legacy – there’s little interest in exploring a franchise if the original source isn’t all that good in the first place.)

But let’s be clear here: the failure of the games and mediocre reactions to The Animatrix would have signaled that this crossing-of-the-media-streams was fatal. Sure, it made money – a lot of money – but it was so complicated and convoluted that by the end of it all, Hollywood rightly thought it wasn’t worth it. It was most likely Harry Potter or Lord of The Rings, the successful book series turned film in 2001 that really turned all that around. Looking at the remnants of The Matrix, everyone learned some valuable lessons – primarily to work with franchises that were already established and easier to comprehend. Coupled with the rise of Comic-Con and geek culture (along with social media), Hollywood specifically realized that utilizing these established fanbases and liberally sprinkling them with controversial BS would be all that was needed to make this bloated, endless machine of summer franchises, arguably made purposely controversial to increase buzz. There’s no way that the Ninja Turtles film will be any good, but every site seems rabidly fascinated with each and every casting call.

From the ashes of The Matrix franchise, came forth the endless stream of loud, riotous, special-effect heavy franchises that rip through theaters and tear-ass across theaters, TV, comics, and video games. Hollywood learned lessons from those burning embers, lessons that now have been taken too far in the wrong direction. Perhaps we need a similar crash-and-burn these days, but I doubt it will be enough to stave off the bloated behemoths coming to theaters in the years to come, and certainly won’t end studio executives mining the dregs of our entertainment past to find the next new endless franchise – I’m pretty sure there will be a Matrix reboot or TV show in the next five years. Yet for a moment, The Matrix was a thing, and we experienced all of it, unwittingly opening a door that we may never close.