Posts Tagged Writing

Tip from Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh is the Young Black Female Lead We Need Right Now

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on August 24, 2016

Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh is based on the Dreamworks film Home, a buggered, incomplete piece of animation that never quite grasped the satirical edge needed to portray the abject and complete removal of citizens into makeshift suburban prisons. Home cared little about the uncomfortable connotation of such a premise, which resulted in a plot – in which a young black girl teams up with an alien outcast to try and find her mother – that could not shake off its racially-coded baggage. I know. I know. I wish I could just ignore the analogies – the wholesale removal of people from their homes, the wholesale removal of African people from their continent, the constant splintering of slave parents from their children to foster an economic system that possesses ramifications that last even till this day. But what you need to understand is that it is so, so hard, and Home did little to ease that discomfort from my mind.

In that regard, I had very few expectations of this show.

If a Home TV series had to be made, the best bet would be to ignore that entire premise and forge onward with new, unrelated storylines. Adventures of Tip and Oh does for the most part, although the occasional exploration of the Bov’s cinematic past actions is as awkward as you’d expect (more on that later). The animation is decent; the character designs are off-putting, as typical of Thurop Van Orman’s style, but functions well enough in movement, and viewers will find themselves getting used to it fairly quickly. The character choices are fairly trope-y and questionable, with Donny being a Mr. Krabs-esque non-entity, Sherzod gearing up to be the most decisive character in a while, and Lucy exhibiting a certain level of air-headedness that doesn’t seem to fit a single mother living in Chicago. These, and other creative decisions, suggest the writers are still working through some issues, but there is one thing that Netflix’s new show has right: Tip herself.

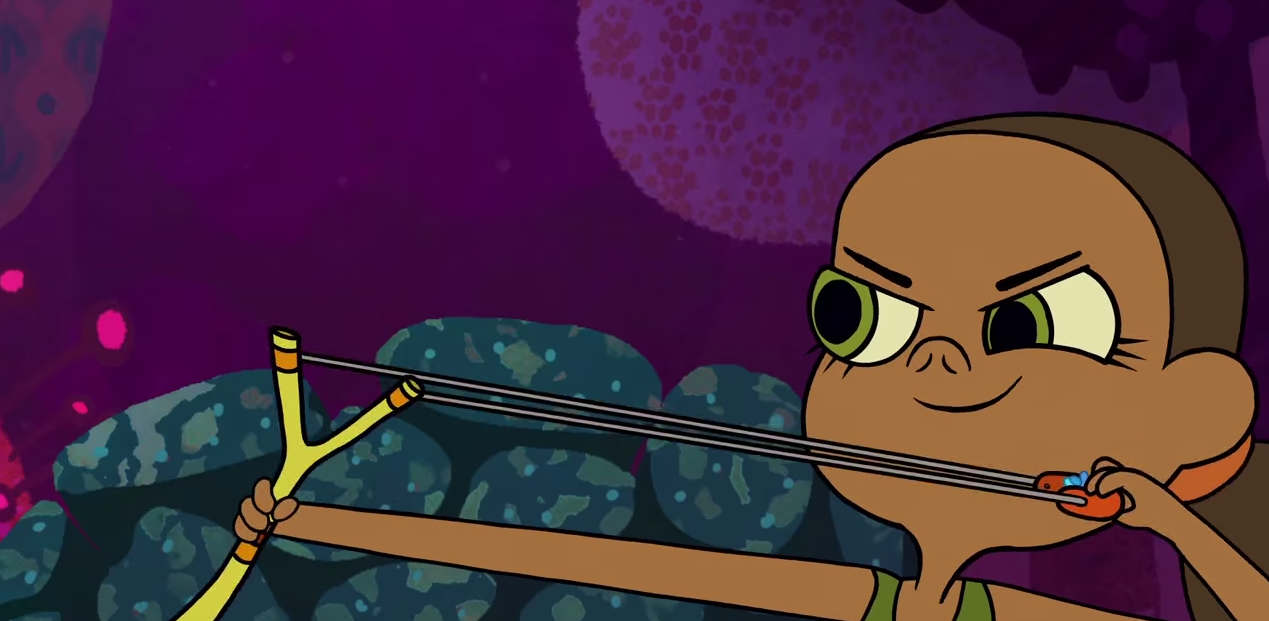

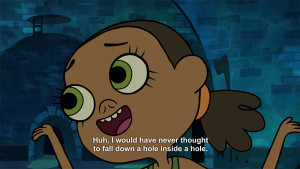

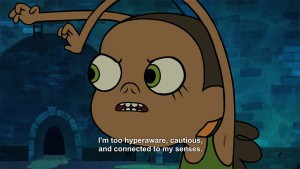

I didn’t warm up to Gratuity “Tip” Tucci at first. She seemed a bit all over the place. She is inconsistent, a bit aggressive, a bit loud, a bit too weird – especially compared to her cinematic counterpart. But then I realized something: that is the point. Tip is purposely, uniquely, her own girl. She is an eighth-grader who possesses her own very limited, very vain, very specific point of view. Her aggressiveness, loudness, and weirdness is uniquely her own. The writing doesn’t quite do her any favors, specifically in terms of the situations that she finds herself (and Oh) in. But Tip herself is special. She is unabashedly herself, not particularly concerned to fit within the parameters of young girl character templates – specifically, young black girl characters – that came before her. She is Penny Pride – clever, determined, confident to a fault – mixed with Star Butterfly – extroverted, adventurous, out-of-her-league. Tip is confused, lost, conceited, goofy, and, yes, even grating. She is all those things – which makes her the best, most important young black female lead for children today.

I need to reiterate something: other than Doc McStuffins – a show for preschoolers – we do not have a single animated show on the air with a black girl as a lead. Mostly cartoons are driven by young boys (or talking animals). There are more shows now with girls as leads, and/or shows with strong feminine characters. But they’re mostly all white (save for Steven Universe’s Garnet, which is another matter entirely). And that is fine. But in this era and in the call for more diversity, it’s telling that, as usual, young black girls are continually, routinely ignored. (Full disclosure: I pitched this piece to a well-known site, which was rejected, and which I deeply believe contributes to this problem.) Seeing and experiencing someone like Tip on my screen felt revelatory. It made me realize how limited in scope my expectations of what young black girls could be. (Note I didn’t say “what black girls should be,” which is an extremely important distinction.) I love Tip because, sometimes, I don’t love Tip. I love that she’s sweet and loving and naive and annoying and too much and quirky and super-weird and sometimes “uppity.” Black girls need to see this. We all need to see this.

This scene epitomizes the kind of person Tip is as a character. There’s no contextual reason why she sniffs herself (they’re in a sewer, but there’s no reason why she sniffs her armpit versus any other part of her body), but it shows her her spirit, vanity, and goofiness all in one brief monologue.

Tip isn’t African-American. She’s Caribbean-American. Her grandparents immigrated from Barbados; Tip is second-generation. The show doesn’t play around too much with this, although it is nice to see when they do. (I would love to see more Barbados-inspired bits on occasion, in the fun ways that Sanjay & Craig sometimes played with its Indian-related bits.) I don’t expect the show to really do that, though, mainly because the writers don’t seem to really grasp the full relevancy of what they have in a character like Tip. There’s theoretically a lot to unpack in a show in which the Bov implemented forced displacement and occupancy, where the setting is Chicago, and where Tip and Lucy live by themselves sans a father figure. When Tip’s grandparents visit in “Wrinkly Humans People,” that awkwardness is palpable, but the writers don’t see it. After all, her grandparents deeply distrust the Bov for what they did, and you honestly can’t blame them. Yet the show works it so as to suggest that it’s her grandparents that are in the wrong, that they’re the ones who are, essentially, the bigots, since they just can’t get over what the Bov did. Well, of course they can’t. History is ugly.

Even still, there is potential here. There is a rich complexity in the idea of Tip’s broader acceptance of the Bov and, specifically, Oh, and how that comes up against the reality of what the Bov did. There is perhaps something to how easily a young Tip has forgiven the Bov in order to maintain the stability of her small family unit, and how that continues to push up against those still harboring resentment towards their occupiers-turned-neighbors. It would be deeply interesting to see episodes in which Tip has to, in some way, address how she justifies her love for Oh, as opposed to her past hatred for the Bov’s role in separating her from her mother. Adventures with Tip and Oh might have been better served ignoring all that overall, but although I do applaud the show for dipping its toe into the thornier sides of the film, I doubt the writers have the temperament to hit such dramatic notes.

That’s a dramatic layer way out of reach for this crew. At this point, in its first season, it would be just enough to take a fun, deep look at Tip herself (in the context of a young black eighth-grader with only a mother living in Chicago). As a unique character, the writers provide her with the variety of traits that I’ve mentioned earlier. As a character who will be developed, that where the writers fall short. It’s tricky, because the show doesn’t need to be an in-depth (if silly) examination on what it means to be a young black girl in Chicago – aliens or not. But it would be worth exploring some of the issues unique to that worldview and experience. The clearest example of this dilemma lies in “Angerdome,” an episode in which Tip deals with her anger. There are volumes of content that could be written that explores the social exploitation and discrimination that exists within the “angry black woman” trope. It is both vicious (which posits all black women as unstable and prone to violence) and commodified (from the lighter-but-overused “sassy” trope, to pushing their angry reactions on reality TV). It’s hard to say how the writers see all of this in “Angerdome,” though. There’s a moment, after various characters tell Tip to calm down, where she proclaims, “I’m allowed to be angry!” and it is wonderful; filled with the personal, determined, defiant spirit that young black girls need to hear. Yet the power of that statement is undercut when, immediately after, Tip resigns to needing help (and an outlet) to deal with her anger.

That’s what makes it hard. There is the real, distinctive lesson which allows kids to understand that having an outlet to deal with anger is important, and I can’t fault the show for dealing with that (although the answer they come up with is muddled). At the same time, the show mostly ignored the opportunity to explore Tip’s individual struggle with what it means to be a black girl who gets, and is allowed to be, angry. It’s a powerful statement that the writers fail to notice as a powerful statement. It’s part of the overall verve of the show, really. It’s great to see Adventures with Tip and Oh use a character like Tip to have fun with the general complexities of childhood, especially within such a specific premise. It’s tougher to see this done separate from the unique characteristics and history that Tip (and the show) embodies: the black, only-child, fatherless, Chicagoan setting. The universal ideas are fun, and pushing them through Tip is wonderful, but the writers have an opportunity to really explore Tip’s experiences at a personal, raw level, and I don’t think the writers see it – or they refuse to.

Still, I praise the fact that a character like Tip exists. She is simultaneously fun and frustrating, and it makes her necessary to see a character like her on television. What ever issues or concerns that may happen around the lives of the Tuccis (which, for all we know, could be fixed by season two), Tip’s goofy, abject, unforgiving weirdness and quirkiness – so often contributed to white women to the point of a dated, oft-misunderstood trope – has been finally applied to a young black girl. It’s just good, refreshing even, to see a black girl outside of a typical “no-nonsense” role. (Tip is no-nonsense, but it’s defined within her weirdness, not as a sole contrast to those “silly” white kids.) A lot of her appeal is due to the voice artist, Rachel Crow, a 2011 X-Factor contender taking the role from Rihanna from the movie. Rihanna had gumption, but at best her voice work was merely passable. Crow brings a serious, specific attitude to Tip – a rough energy that’s wonderfully infectious (in the same multi-layered cadences that the late Christine Cavanaugh gave to Gosalyn Mallard). She also has a distinct singing voice that manages to add flavor to both the show and the character, without it being too distracting or random.

So flaws and all, I look forward to see where Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh takes Oh and Tip in future stories. The creative critic in me wants to see the show lean a little harder on its premise, on its boundaries and issues, just to see them contextualize how Tip might respond to those tougher dilemmas and grow as a person. I would love to see those issues hit upon, to expose it to kids, particularly young black girls, who struggle through those issues every day. As for now though, I just want to see more Tip. I want to see more of her odd, assertive, annoying behavior. I want to be challenged, bothered, and amused by Tip’s antics, because I want young black girls – and all viewers, really – to understand that being like Tip is okay.

(Final note: I know this is “just a cartoon.” I know I should just enjoy it for what it is. What I’m telling you is, I just can’t. Not with what I know and experienced, not with what I’ve read, not with the history and context of this country and even Chicago itself inside my head, not with the news stories and the personal accounts of people’s experiences shared every single day. I physically, emotionally, psychological cannot separate the two. I can only channel it, and I would hope and love to see Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh do this as well.)

Zootopia’s Runaway Success, and the Disney Afternoon Connection

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Film, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on June 22, 2016

Alan Young passed away on may 19, 2016. To many, he was the lead farmer who could communicate with talking horses on Mr. Ed. To others, he was the perennial voice of Scrooge McDuck in Ducktales, the irascible richest duck in the world who led the way for one hundred episodes, one theatrical film, a number of classic and modern shorts, and even in the Nintendo reboot of the Capcom game. Young’s passing was memorialized by many of those who worked with him in TV, film, and gaming, yet in terms of the animation community at large, both creators and critics were mostly silent. It was a widely mute, seemingly moot passing: a death of the lead of what could arguably be the most important, game-changing cartoon in the last twenty-five years. Yet it’s representative of the general malaise, it seems, of the pop cultural response and respect to Disney’s 1980s-1990s animated output, which we could call The Disney Afternoon*.

I mention the Disney Afternoon for a reason. The kinds of cartoons that Disney produced – from the two cutsey-yet-complex starters The Wuzzles and The Adventures of Gummi Bears, to the TV show versions of Aladdin and The Lion King – really weren’t what we think of cartoons these days, or even what we thought of cartoons back then. In our current culture, we think of cartoons in sort of broad categories: wacky, silly, and childish; action and (super)heroic; adult and poignant; adult and absurd. Disney’s cartoons, however much they leaned into any of those categories, were anything but. At their core, the Disney Afternoon lineup were driven by adventure, specifically by strong, specific, and non-human characters who sought items, emblems, villains, and icons across multiple locales that thrived with an unique locality and ecology all its own. They were truly their own thing: the cuddly Gummi Bears with their thriving, complex society; the talented-yet-lazy ursine pilot with a surrogate son and a fussy-yet-determined boss; the team of rodents who actively sought to help others as they struggled to help themselves. Even as the quality of the shows varied throughout the years, the core nature of these shows thrived with exaggerated characters who were never-the-less grounded with real emotions, in worlds that only touched upon what could be possible in their unique, respective universes.

*******

There’s been a lot of shock and surprise over Zootopia’s runaway success, the only original animated Disney film to gross over a billion dollars globally since Frozen, and it’s been admittedly a bit frustrating to see how people both misinterpret the movie and/or downplay its proven success. I’ve seen a lot of explanations and theories that I’ve disagree with (the “night-howlers as crack” being particularly insidious), but what prompted me to write this was this fairly dismissive piece. Mr. Spiegel is a fine writer, but the impression I get is that instead of praising Zootopia’s success and offering a credible theory as to why it’s been a global box-office draw, he dismisses the billion-dollar revenue as a new normal, a “non-event.” Which is… pretty disingenuous. As of this point, only Marvel properties have hit the billion dollar mark on their own, as well as a handful of Disney properties (give or take a Minions, which success is couched more in its universality and less in its quality). Not only has Zootopia resonated with audiences across the world, it has incredible rave reviews; yet, at the same time, those reviewers, along with Spiegel, seem flabbergasted to place the film’s success in any context. Spiegel mentions how Zootopia lacks any real Disney World or Disneyland presence, which mainly speaks to Disney’s surprise that the film did so well, not to the “perplexing” nature of the film not gaining much cultural permeation (although I would argue it has, particularly on social media).

Spiegel’s confusion is understandable. The creators and directors of Zootopia often cite Robin Hood as the example in which the film draws its inspiration, and no one could argue that. Yet I feel like Zootopia also draws a tremendous amount of inspiration from The Disney Afternoon, shows often staring talking animals of a various sort in vibrant environments, shows that were also surprisingly deep and complex and meaningful in small ways. And these shows also lack cultural permanence as well. They are rarely showcased at Disney World or Disneyland. They are not quoted on social media or often gif’d or cited as inspiration by many of today’s current batch of animators (I have yet to see an interview with Byron Howard or Rich Moore that brought up TaleSpin as an inspiration, a show that might have well have taken place in 1920-Zootopia.) These are shows that are regularly taken down from Youtube and, until recently, only had (semi-incomplete) DVD releases. Zootopia’s lack of cultural permanence mimics that of the Disney Afternoon’s cultural permanence.

Yet I would argue that Zootopia’s success is exactly due to an audience that’s craving that kind of entertainment – films and/or TV shows driven by an adventurous spirit, led by non-human characters who feel grounded, real, and relatable, all within out-sized worlds that connect to our worlds in more ways than one. The aesthetics and atmosphere of Zootopia fit squarely within the aesthetics and atmospheres of the various Disney Afternoon cartoons: they may not match one-to-one, but they all possess similar criteria: strong, flawed, non-human characters; bursts of silliness mixed with raw, poignant moments; adventure-driven stories that far surpass the need for excessive silliness or wackiness; strong, detailed visuals and proportional character designs; clever uses of pop cultural references that neither stop the flow of the story or interrupt the proceedings for the easy gag. And even though the elements of both the film and the classic animated line-up seem absent from all social cachet, I think audiences are craving it. Viewers are way more open to the kind of entertainment they can find solace in as nerd spaces open up: Steven Universe and My Little Pony and the myriad of superhero films have expanded fanbases considerably. Back in the 90s, small but dedicated fans wanted to live in Gummi Glen, Saint Canard, or Cape Suzette**. Today’s audiences can add Zootopia to that list.

I believe this is what Dreamworks attempted to do in the 2000s. As the less-respected studio began netting large scale success with Kung Fu Panda and How to Train Your Dragon (another movie that seemed to have legs, financially), the studio sought to expand their visual worlds and rich characterizations onto the small screen. For a little while, it was a success, with Penguins of Madagascar a solid hit for Nickelodeon, which could be categorized as a wackier version of Rescue Rangers. Kung Fu Panda: Legends of Awesomeness was a solid follow-up, and Dreamworks followed that up with the Dragons series and Monsters vs. Aliens. But it became clear that Nickelodeon interference, combined with the limitations of the TV CGI landscape, deeply held things back. Nick never established a full Dreamworks block (Dragons went to CN, which promptly burned off the show, which was egregiously boring anyway). Kung Fu Panda, potentially closer to Darkwing Duck’s sensibility (a few writers wrote for both shows!), squandered its potential by leaning way too hard on its lead’s silliness instead of adequately building up its cast and its Valley of Peace locale. Monsters Vs. Aliens just wasn’t good. Given the deal between Dreamworks and Netflix soon after, Nick basically decided to cut its loses and moved on. (And no, the Dreamworks shows on Netflix have not quite matched the aesthetics of the Disney Afternoon.)

I’m not even sure it would have mattered. Dreamworks’ shows have yet to capture cultural permeation either. Except for perhaps Shrek memes, not a single show, either one Netflix or Nickelodeon, seems particularly discussed anywhere, despite the accepted fact that Dreamworks’ television decision is apparently still financially viable. All Hail King Julian has gotten the occasional note in the media, and most recently, Voltron has gotten the social landscape talking. All Hail King Julian sort of resembles Marsupilami, in that it’s focused on the antics of forest-based critters, but with bursts of cultural/social commentary that’s extremely hit or miss. (It actually functions better the rare times it focuses on its characters and pushes them in unique, new, personal directions, but it’s unfortunately pretty rare). And Volton, despite its high quality, doesn’t adhere to any of the Disney Afternoon aesthetics. The other various Netflix Dreamworks shows: Puss in Boots, Turbo FAST, Dragons (which moved from CN a few years ago), arguably do adhere to those aesthetics, but vary in quality and lacks cultural permeation. The former point really smothers up the latter.

It’s that point, which leaves Dreamworks’ programs scattered, random, and unregulated, that seems to allow Disney the opportunity to return to the Disney Afternoon glory. Not only is Disney rebooting Ducktales, but they also are working on TV shows based on Tangled and Big Hero 6. The latter two shows are human based, but, as they are based on some of Disney’s more successful animated films, they most resemble the 90s television takes on The Little Mermaid and Aladdin. I also don’t think it’s no coincidence that Ducktales, Rescue Rangers, and TaleSpin were recently released on iTunes, in their entirety (except for one lone Ducktales episode). In addition, there’s the new Darkwing Duck comic that’s happening. In mostly all those cases, these shows and announcements lack cultural permeation, but it would be a grave mistake to assume that means they lack an audience or a fanbase. Zootopia and its success is not an outlier, or an excuse to toss aside the significance of a global billion dollar draw. It’s an opportunity to examine the very content and context of Zootopia itself, and realize that the world is craving a very specific type of cartoon, one that died out so many years ago.

* to clarify, many of the early cartoons within the Disney Afternoon lineup were originally Saturday morning network-syndicated cartoons, before they were re-packaged as an after-school lineup in the 90s.

** the stylistic nature of the Disney Afternoon show could be a bit more malleable – Darkwing Duck and Bonkers were “wackier” than Ducktales, which itself was looser than TaleSpin – but even in all those cases, fully-realized characters and fully-realized worlds were still firmly established.

Zootopia, Day 5 – The Actual Review!

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Film, Uncategorized, Writing on March 11, 2016

Many people weren’t quite expecting the depths and intrinsic social commentary within this film. Zootopia, Disney’s 55th animated film, stars a young, idealistic bunny named Judy Hopps who moves to the large-scaled city of Zootopia to become the world’s first (furst?) bunny police officer. She learns that’s not as easy as she thinks, getting caught up in a city-wided conspiracy with a con artist fox named Nick Wilde. The two of them form an endearing buddy-cop team that’s both exciting and endearing; critics cite 48 Hours or Lethal Weapon as a clear precedent, but it’s more evocative of Robin Hood by way of In the Heat of the Night.

Byron Howard (Tangled) and Rich Moore (Wreck-It Ralph), and co-writers Jared Bush and Phil Johnston, bring life and vitality to a world of anthropomorphic animals that functions in a brilliant, detailed way. Sharp facial expressions and active body movements gives every walking, talking piece of fauna a real sense of place and personality, particular the various ways in which Judy both expresses and fails to express her emotional state. The world itself comes together in a way that’s never quite been expressed before in a film like this; the opening sequence in which Judy travels by train to Zootopia is one of the most emotionally and visually unique “newcomer heading into town” montages ever put to celluloid, with contrasting landscapes (forest, savannah, tundra) butted up against each other, yet logically designed by what seems to be incredibly advances in animal science.

There’s two clear ideas here that are working together (and, at times, against) each other here, outside of the talking animal concept. The first is the actual mystery at play, and the second is the interplay of the various species and species designation at work. There’s a basic kidnapping that needs to be investigated and solved (the basics of every procedural ever), and the social context that this mystery takes place in. For the most part the movie manages to balance both those elements with a relative deftness that even the most well-known films of that caliber manage to do. On the whole, though, the actual mystery, while solid, has a bit of a wonky, beat-by-beat formula to it: Nick and Judy find a clue, then there are shenanigans, then there’s another clue. It’s normal in the scheme of procedurals since the dawn of television time, but it would have been nice to see some sort of variation on those rhythms, or at the very least more in-world exploration through the clues themselves. An interview with an injured witness comes off flatter than it should, since it takes place in an empty, desolate region that, thirty minutes earlier, was brimming with life and energy. Never hearing from the injured party again is also a disservice, but then again, its part of the procedural MO. It fits.

The plotting of the central conspiracy also fits within the nature of “big twists” that has been part of the recent batch of Disney films, from Frozen to Wreck-It Ralph to Big Hero 6. In this case, however, the mystery and the twist are tied into the film’s trenchant, specific observations about the messy, complex relationships of the various species of its world. This is usually where fellow critics slip up, often trying to find one-to-one allegorical connections between species relationships and human-racial ones. It’s a metaphor that fails in that regard because Zootopia knows and understands the levels and layers through which is citizens must work through. It’s not just about predator vs. prey: it’s about the differences of species (fox vs. bunnies, lion vs. sheep, or lamb), of the nature of power structures (and the abuse/manipulations of which), of stereotypes, of nature vs. nurture, and of intrinsic abilities and acknowledging the full comprehension of a person, based on species, classification, gender, and class.

It’s on this point where the movie shines. The two short flashbacks define how Judy and Nick function in the present day with a direct, pointed nuance that even live-action, Award-winning films completely miss (I’m looking at you, Crash). Zootopia focuses on the bunny and fox’s relationship, particularly how their pasts inform their present, not just in the specific incidents that mark them for life, but in the implications of the dialogue and visuals around them. Avoiding spoilers, it’s important to pay specific attention to how certain characters around them react and respond to their circumstances, and then how it informs them in scenes within the present day.

Zootopia’s visual palette and sound design is gorgeous: bright, vibrant backgrounds and functional landscapes fill every frame, along with an enjoyable (if not particularly distinct) score and soundtrack that really adds to the film’s atmosphere (with all due respect to Shakira, her “Try Everything” song and Gazelle character feels forced in a way that only fits within the context of the film). It’s those tiny details – the horror-tinged Cliffside facility, the lived-in, worn-out government offices, the assortment of crowd actions in a final concert scene – that makes Zootopia feel alive and personable.

Zootopia isn’t perfect. The pacing for the first hour is a bit rushed and wonky, and there’s definitive narrative shortcuts that the film uses to get from one plot point to the next. But there’s a section of the film in the middle that’s pretty much perfect, an excellent set of scenes that exposes a broken, misguided vulnerability from both Nick and Judy that reflects the real world in a way that’s rarely seen on TV or film. It’s one of the strongest, most socially relevant lessons that works for both kids and adults, with just enough self-awareness to keep the broad strokes light and entertaining. The jokes go from silly physical pratfalls for the young ones to the solid, perfectly-timed gags that adults will catch immediately (or, better yet, on the second or third viewing). Yet it’s Judy and Nick, voiced by Ginnifer Goodwin and Jason Bateman respectively, who keeps the world from spinning out of control. Life is messy, and Zootopia never suggests its an easy fix, but the attempt is not only worth the effort, it’s necessary.